Bloodletting (Venesection) During the Civil War

After reviewing an inventory list of medical supplies from a N.Y. military hospital at the end of the War, the presence of scarificators in the inventory lead to this investigation of evidence in the military literature of bloodletting being in use during the War. From examination of the literature gathered from the Medical and Surgical History citations, venesection was indeed practice during the Civil War, but was rapidly being abandoned as the War years progressed and knowledge of medicine and bleeding wounds increased.

In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America, many symptoms of illness were believed to be caused by an excess of blood: the removal of some was therefore thought to alleviate the condition. There were two main methods of bloodletting: using leeches and venesection (i.e. cutting open a vein). Bloodletting is achieved by fleams, scarificators, cupping glasses, leeches, and assorted instruments.

Venesection (or phlebotomy) was the technique of lancing open a vein to remove blood, which could be drained into a bowl. It could also be removed by suction using a bloodletting cup in which was burned a small amount of alcohol to create a vacuum. Leeches are annelid worms that inhabit fresh water. They are injurious to animals and people from whom they suck blood. They attach themselves by means of their strong mouth adapted to sucking. The medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis, was employed on "bleeding" patients. It is still used for some medical purposes and is a source of the anticoagulant, hirudin.

If you search for 'bloodletting' in the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion not that much shows up. However if you search for 'venesection', then many citations pro and con as well as actual cases are found.

There is abundant evidence reported of the earlier use of bloodletting and bleeding in the History, but only two cases of actual "bloodletting". The problem is with the term: bloodletting. The term used by surgeons at the time was 'venesection', not the older term 'bloodletting'. Most of the information is in defense or rebuke of the process, not the actually use nor which instruments were used unless reference was made to a specific procedure like cupping or leeches.

Examples in the defense of bloodletting or venesection is found thorough out the various medical reports, much of which is from pre-War literature. Of note is the adamant advice from the Confederate medical leaders that bloodletting should be avoided for various treatments.

The bottom-line is bloodletting or venesection was practiced through out the Civil War, because when the War started, bleeding was an accepted practice in the medical community. As the war progressed, evidence based treatment was leaning against the use of bleeding for various medical or surgical problems as reported in the Medical and Surgical History.

Edited from the medical text book Handbook of Surgical Operations, 1863, (in this collection) written during the Civil War by Stephen Smith, M.D.:

BLOODLETTING: The abstraction of blood is divided into general and local bleeding.

General Bleeding.—In general bleeding, blood may be drawn from the veins, when the operation is called venesection; or from the arteries, when it is known as arteriotomy.

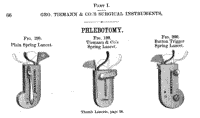

Lancets differ as to their points; some are very blunt, others are very acute- the more obtuse are generally used when the vessel is superficial, and the more acute when it is deeply seated.

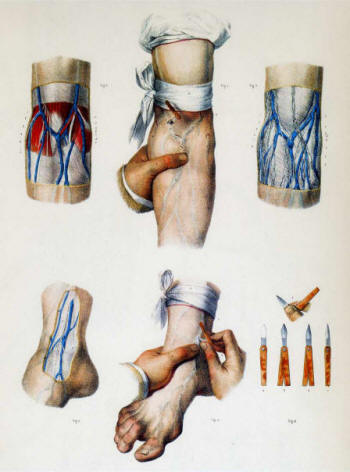

Venesection.—Blood may be taken from any of the superficial veins, but those of the neck, the bend of the arm, and at the ankle, are generally selected. The patient may be seated or recumbent, but in general the position should be chosen which most enlarges the vessels. The operation should commence by stopping the flow of blood to the heart by a ligature applied around the part on the proximal side of the point selected for the operation, sufficiently firm to close the veins and still leave the arteries unobstructed. The veins now become prominent unless the person is very fleshy, when the position of the vein must be determined by its corded feel. The operation is performed by placing the thumb of the left hand firmly on the vein (Fig. 40), a little to the distal side, to prevent the vessel from rolling aside on the attempt to puncture it. The lancet, held-between the thumb and index finger of the right hand, the blade at an obtuse angle with the hand, is plunged into the vein obliquely to its transverse diameter, and the hand being fixed, the point of the lancet is elevated so as to cut its way out.

The success of the operation is determined by the flow; if this should be slight, it may be due to too small an orifice, which should then be enlarged; or to a mass of protruding fat, which may be pushed aside. If an increased flow is required the patient should be directed to grasp repeatedly the staff, or the operator may rub the limb from the wrist towards the elbow.

When the proper amount of blood is drawn the band should be removed, and a small compress being placed over the wound, a figure-of-eight bandage is applied;. to prevent air entering the circulation in bleeding from the jugular, pressure on the wound should be made before the compress is removed.

Venesection is generally performed either on the external jugular, the median basilic or cephalic, or the internal saphena.

External Jugular.—A compress is placed over the vein in the supra-clavicular fossa, and firmly retained by a bandage passed over it and under the opposite axilla; the index finger of the left hand is placed upon the vein above, and the incision is made upwards and outwards across the platysma myoides.

Median Basilic and Cephalic.—The cephalic vein may be selected on account of its isolation. The basilic is the largest, but the brachial artery passing directly under it is in danger of being wounded. The position of the artery must first be determined. A band is then passed firmly around the arm, above the elbow, and with his band the patient grasps a staff. The operator, standing in front of the patient, grasps the arm with the left hand, placing the thumb on the distended vein, and the fingers on the back of the elbow, and holding the lancet in the right, opens the vessel.

Internal Saphena.—The foot is first placed in a vessel of warm water to distend the veins; a band is then passed around the leg, just above the malleoli; the thumb being placed on the vein it is opened just above the inner ankle, with an oblique incision.

Arteriotomy.—The temporal artery is that on which this operation is practised. It may be opened just over the zygoma, in front of the tragus, before its division into the anterior .and posterior branches, but the anterior branch is generally selected. The position of the artery is determined by its pulsations; the skin being made tense a straight incision is made with a scalpel, involving a part of the caliber of the vessel; when a sufficient amount of blood has been withdrawn the artery should be completely divided, and compression made on either side of the incision with small graduated compresses, firmly retained with a bandage.

Local Bleeding.—The local abstraction of blood is effected by leeching, cupping, scarification, and punctures.

Leeching.—Leeches should not be applied to parts liable to infiltration of blood, and discoloration, as the eyelids, scrotum, prepuce, or where a wound would disfigure, as their bites sometimes leave scars, nor over the track of a superficial vein. They are best applied by placing them in a small glass vessel, and inverting it over the inflamed part; blood, or sweetened milk, is often put on the skin. A single leech can take about an ounce of blood. When removed, the parts may be fomented to increase the flow; if it is desired to stop the blood the bites may be sprinkled with flour, starch, or other absorbent material; if the flow of blood continues astringents are used, of which the best is the persulphate of iron.

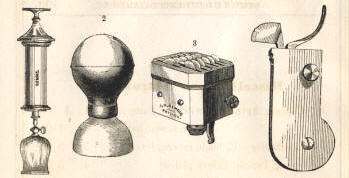

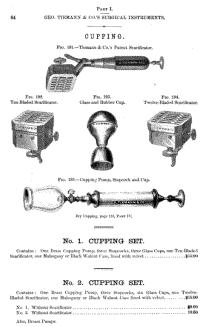

Cupping.—Cupping requires a scarificator and cupping-glass. The scarificator is an instrument containing eight or twelve blades, moved by a single spring, and so arranged as to be readily graduated as to the depth which they shall penetrate. They cover but the small space of an inch and a half or two inches square, and make eight, twelve, or more parallel cuts. The cupping-glass .may be simple tin or glass, of the proper size and shape, and applied by exhausting air within by burning a few drops of alcohol; or it may have an exhausting pump attached to the top ; or, finally, it may have an india-rubber top, which requires only to be squeezed to produce a vacuum. The latter cups have but lately come into use, and are preferable to any other.

Scarification.—In making scarifications, the lancet, scalpel, or bistoury should be used, and the cuts should be made only partially or entirely through the skin, as may be necessary to promote the local abstraction of blood. The incisions should generally be made the entire length of the inflamed part, and within an inch of each other. The flow of blood may be greatly increased by warm fomentations.

Puncturing.—Punctures are made with a straight sharp-pointed bistoury, or a common lancet. The instrument is thrust into the inflamed tissues, to a depth varying from an eighth of an inch to an inch, carefully avoiding vessels and nerves. They should' be repeated until the entire surface is relieved of tension. Warm fomentations will increase the depleting effect.

Click images to enlarge

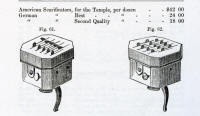

Bloodletting instruments by Gemrig c.1866:

Glass cupping apparatus with brass air pump

Cupping apparatus with elastic bulb

12 blade brass and steel scarificator

One blade spring lancet

Cupping & lancet instruments shown in the c.1867 Tiemann catalogue

Additional information on this 'thumb lancet' set by Geo.Tiemann

______________________

Army specified contents of a pocket case during the Civil War

Source: "The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. (1861-65.) Part III, Volume II, Chapter XIV.--The Medical Staff and Materia Chirugica"

"The Pocket Case contained: 1 scalpel, 3 bistouries, 1 tenotome, 1 gum lancet, 2 thumb lancets, 1 razor (small), 1 artery forceps, 1 dressing forceps, 1 artery needle, 6 surgeon's needles, 1 exploring needle, 1 tenaculum, 1 scissors, 1 director, 3 probes, 1 caustic holder, 1 silver catheter (compound), 6 yards suture wire (iron), ¼ oz. ligature silk, 1/8 oz. wax, 1 Russia leather case."

_________________________

Proof: Citations in the Medical and Surgical History of the Rebellion

Citations from the Medical/Surgical History--Part I, Volume II

Chapter I.--Wounds And Injuries Of The Head.

Section II.--Miscellaneous Injuries.

A warning to avoid bloodletting from the CSA:December, 1862, of an aggregate of 48,543 patients in the General Hospitals under the supervision of Surgeon T. H. Williams, C. S. A., there were sixteen examples of concussion of the brain. All of these thirty-four cases terminated favorably. From the absence; in these reports, of any fatal results from concussion, it may be inferred such were probably entered under other headings. Of the Confederate systematic writers on military surgery, the compilers of the official manual(1) advise, in the early treatment of concussion, the use of external warmth, frictions, and diffusible stimuli; Surgeon J. J. Chisolm(2), C. S. A., thinks "the safest practice consists in doing as little as possible, the indiscriminate use of stimuli on the one hand, or bloodletting on the other, being especially avoided;" while the Surgeon General of North Carolina, E. Warren,(3) with strange confusion, "in order that the pathological difference between concussion and compression of the brain may be thoroughly comprehended," ascribes to concussion the signs almost universally believed to attend compression. The "Confederate States Medical and Surgical Journal," published under the auspices of Surgeon General S. P. Moore, C. S. A., contains no reference to the treatment of concussion of the brain, and the reports and treatises above alluded to furnish the scanty information to be derived from the Confederate records.

Among the Confederate writers, Dr. E. Warren (op. cit., p. 370) observes that "wounds of the lung are far from being so fatal as might be supposed in advance. Numerous cases have come under my own observation, during the present war, in which rapid recoveries have followed the most severe penetrating wounds of this delicate organ. The experience of Confederate surgeons will confirm the assertion that unless death speedily results from haemorrhage or collapse, a favorable prognosis may be formed in a majority of such cases." The writer does not indicate the degree of fatality which might be erroneously "supposed in advance," nor describe the numerous recoveries he has witnessed after the most severe lung wounds, and the recorded experience of Confederate surgeons invalidates instead of confirming the assertion that the majority of severe lung wounds get well. Dr. J. J. Chisolm (op. cit., p. 310) says: "Wounds of the chest, when taken as a class, are, perhaps, the most fatal of gunshot wounds. Should the lung be severely injured, the case usually terminates fatally." He then relates some remarkable examples of recovery, and adds: "In our experience, penetrating wounds of the chest, even those in which the ball had clearly traversed the lung, are, by no means, so fatal an injury as gunshot wounds of other regions of the trunk." The apparent contradiction is avoided by the limitation of the comparison to wounds of the abdomen, Pelvis, and spine. "Under the expectant plan of treatment," Dr. Chisolm continues, "which consists of little more than careful nursing, avoiding all active treatment, more especially bloodletting, we have succeeded in saving a majority of our wounded. Surgeon Them, in a recent report to the association of army and gives a list of seventy-four cases of gunshot wounds perforating the chest and transfixing the lungs, as reported by Confederate army surgeons. Of these, twenty died.--a mortality of 25 per cent.,--which indicates clearly the advantages of the expectant course of treatment for this as well as for all gunshot wounds, over the heroic and fatal treatment of former years.As far as could be ascertained, bloodletting had been resorted to in but one case of perforated chest wounds." On referring to the abstract of the report of Surgeon Them, chairman of the committee on gunshot wounds of the chest, as printed in the Transactions of the Association of Army and Navy Surgeons, at page 60, of the April, 1864, number of the Confederate States Medical and Surgical Journal, it is found that, after a preliminary dissertation on "the general treatment of injuries of the lungs from missiles, penetrating and cutting weapons; the time and manner of death under such circumstances; the pathological condition, functional embarrassment, or usefulness remaining after these accidents; the mode of production and treatment of emphysema; and the provisions made by nature for accommodating foreign bodies retained within these organs, with the amount of disturbance which ensues," Dr. Them "regretted that few replies had been received to the interrogatories which the preparation of this report had suggested, and that he could furnish only seventy-four cases of gunshot wounds of the lungs, in which twenty recovered, from which limited number it appeared the mortality was little over twenty-five per cent., or one-quarter. As far as could be ascertained, bleeding had been resorted to in but one case, and that recovered."

Justification for bloodletting prior to and after the War:BAUER--Krankheiten des Peritonaeums, Ziemssen's Handb., Bd. VIII, 2, S. 355--after stating that the approved treatment of peritonitis has consisted in venesection, the application of leeches to the part, inunctions with mercurial ointment, sometimes to salivation, and the internal administration of calomel, adds: "I must avow that I have not been able to recognize any demonstrable success from these things; that on the contrary the free abstraction of blood from the abdomen by 50 or more leeches must produce an injurious effect on the circulation. At most it may be claimed for a smaller number of leeches (15-20) that the subjective sensations are improved without any injurious consequence resulting. But I believe that in most cases the practitioner may omit local bloodletting without being guilty of neglect." In striking contrast with these temperate views are those expressed in a recently published lecture by my friend H. C. WOOD, JR.--The heroic treatment of idiopathic peritonitis, The Boston Med. and Surg. Jour., Vol. XCVIII, 1878, p. 536: "I remember my uncle, Dr. George B. Wood, saying that he never lost a case of peritonitis in an adult, and the reason he gave was that he always bled his patients from the arm until they fainted, and then put one hundred leeches on the abdomen. I am proud to say that I am a thorough believer in the same plan of treatment, antiquated as it may appear. I have never, you see, had cause to regret having bled my patients copiously. It makes very little difference whether you take the blood from the arm or from the abdomen, provided you draw enough to make a profound impression.

HEUBNER--S. 543, op. cit., p. 529, supra: "Der Aderlass, früher (von Sydenham, Broussais u. A.) viel angewandt, wird jetzt mit Recht voll-ständig vermieden.' AITKEN--Vol. II, p. 659, op. cit, p. 647, supra: "Bloodletting has now been totally superseded and rendered unnecessary by the use of ipecacuanha." But ipecacuanha was used with equal freedom in the latter part of the seventeenth and during the eighteenth century, even by those who bled extravagantly, as we will see hereafter. In this connection I must commend the prudent remarks of STILLÉ--p. 363, op. cit., p. 650, supra--which were doubtless not without influence upon our medical officers. He declares that under the use of antiphlogistic measures in dysentery "the strength is very apt to fail suddenly, and the disease to assume a low asthenic type. Hence the apparently clear indication for venesection in the necessity of allaying the general violence of action and the local distress is calculated only to mislead, as it has done many physicians who afterward abandoned it as mischievous."

S. D. GROSS--A discourse on bloodletting considered as a therapeutic agent, Trans. of the Amer. Med. Ass., Vol. XXVI, 1875, p. 419. In this address bloodletting is deplored as "one of the lost arts." The author declares that for nearly two thousand years it was regarded by the most eminent and enlightened men as essential to success in the treatment of disease. But the historical sketch just presented shows that this remark does not apply to the use of the operation in dysentery. Our modern practice in this disease is in harmony with that of the greatest of the Greek physicians, and is supported by the testimony of some of the best observers in every age. I cannot therefore believe that in this disease "bleeding will again come into fashion," p. 432.

Discussion of using leeches for bleeding:When the use of cups and leeches in dysentery was again revived they were employed not merely as a substitute for venesection, but also as an additional .means of depletion. The Arabian prejudice against applying wet cups to the abdomen no longer exercised any restraining influence, and this brutal mode of depletion, commended by various writers from Fournier and Vaidy to Barrallier, has been extensively used.(§) I am sorry to say that it was resorted to by a few of our own medical officers during the civil war.(||) The application of wet cups to the sacral region, when pain in that part is complained of, or when rectal or vesical tenesmus is urgent, has also been approved by some physicians.(p) But, on the whole, during the present century preference has been given to leeches as a means of local bloodletting in dysentery, and cups have generally been employed only when economy was an object, or when leeches were difficult to obtain.

The application of leeches to the anus, proposed by Buchner in the early part of the last century, and approved by Pinel towards its close, was extravagantly praised by Broussais,(**) and came subsequently into very general use, especially in France. This plan has been commended by many modern writers, among others by Savignac, and quite recently by Heubner.(++) It has been claimed that the congested circulation of the mucous membrane of the large intestine can in this way be directly depleted.

Citation evidence of use of bloodletting or venesection during the War:

General bloodletting appears to have been tried in two cases: In 25 the abstraction of eighteen ounces was followed by decided improvement, which continued for some time under quinine, but death took place in a relapse; in 24 the removal of twenty-four and afterwards of sixteen ounces of black blood had no influence in postponing the fatal issue and but little in relieving the restless delirium. Regarding the disease as primarily a meningitis, JONES recommends bleeding to faintness, cups, purgatives and mercury, with quinine and opium during the active period; but as his pathological views are manifestly incorrect, the treatment by general bleeding cannot be accepted unless supported by better results than have hitherto been brought forward.

(*) See the case of Corporal Joseph B. Grow and that reported by W. S. ARMSTRONG, of Mobile, Ala., supra, p. 595.

(+) Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol. LXXIlI, 1866, p. 253.

(++) American Jour. Med. Sciences, Vol. XLIX, 1865, p. 17,----Opium, however, was in common use in the treatment of this disease as early as the begin-ruing of this century. See STILLÉ, On Epidemic Meningitis, Philadelphia, 1867, p. 154.

Surgeon M. R. GAGE, 25th Wis., March 31, 1863.--In most cases this disease is ushered in by slight or severe chills, soon followed by increased heat of surface and severe febrile symptoms. There will also be found often pain in the loins and a stitch in one or both sides of the chest, accompanied with cough, and in many cases dyspnoea and great pectoral oppression. In the beginning the cough will be dry and harsh, but there soon appears a frothy mucous expectoration, which becomes in a short time the rust-colored sputa so characteristic of this complaint. A full and bounding pulse shows the excited state of the circulation. If the case be ushered in with symptoms of great severity venesection is promptly resorted to and is, we believe, the only reliable means of arresting or controlling the disease. The bleeding should not be stinted but liberal; a large opening should be made in the vein and a full, free stream allowed to flow until syncope is established. This course, it must be understood, is applicable only to those who are healthy and plethoric, and when the onset of the affection threatens imminent peril to the integrity of the organs attacked. In the case of a feeble constitution, or when the pulmonary organs are already affected by tuberculosis, there would be doubt as to the propriety of bloodletting, or, if decided Upon, a manifest impropriety in carrying it to the extent just indicated. After the bleeding tartar emetic is administered ad nauseam; cathartics may also be brought into requisition, and are invaluable adjuncts in pursuing the treatment already shadowed forth: Dover's powder, ipecacuanha and calomel, in alterative doses, are of the first importance in assisting the efforts of nature to clear the affected lung from the inflammatory products deposited in the air-cells. Cupping over the pectoral region may be <ms_p3v1_809>employed in the early stages to good advantage; benefit may also be derived from the application of sinapisms and at a later period from blisters. The patient toward the end of the attack may require a supporting course, such as beef-tea, wine, quinine, etc. [During the quarter ending March 31, 1863, Surgeon GAGE treated in his regimental hospital eighty-eight cases of pneumonia, six of which terminated fatally.]

Venesection discussions:

Medical/Surgical History--Part I, Volume II

Chapter I.--Wounds And Injuries Of The Head.

Section II.--Miscellaneous Injuries.

Severe commotion or concussion of the brain was observed in fifty-nine of the seventy-two cases of the second class, or, altogether, in seventy--four of the four hundred and three cases of miscellaneous injuries of the head without fracture. The treatment of this condition usually consisted in wrapping the patient in hot blankets, and applying bottles of hot water to the extremities, in employing frictions, and sinapisms, and stimulating enemata; and, after reaction was established, in prescribing purgatives, low diet, and rest in bed. The precautions suggested by authors respecting the use of volatile salts, cordials, and venesection during the stage of collapse, appear to have been observed uniformly. The management of the stage of reaction appears, also, as a general rule, to have been prudent and judicious; but many exceptions, due sometimes to the exigencies of the situation, and sometimes to the negligence or officiousness of the attendants, are notified, in which quiet and abstinence were not enjoined, or stimulants and full diet were ordered in obedience to false therapeutic dogmas in preference to the lessons of experience.

To these causes, probably, must be attributed the considerable number of instances in which concussion was followed by cerebral irritation or encephalitis, complications which will be considered further on. In one case of concussion, (SHERMAN, p. 41,) when reaction was becoming over-action, venesection was practiced, with apparent advantage.

Medical/Surgical History--Part I, Volume II

Chapter V.--Wounds And Injuries Of The Chest.

Section II.--Gunshot Wounds Of The Chest.

Citations which used venesection:

CASE.--Private Andrew G----, Co. I, 5th Michigan Volunteers, aged 21 years, was wounded at Fredericksburg, December 13th, 1862, by a missile, which fractured the clavicle, passed through the apex of the right lung, and emerged near the eighth dorsal vertebra. He was admitted to Harewood Hospital, Washington, on December 17th, suffering from traumatic pneumonia, the more formidable symptoms of which appeared to be relieved under venesection, and the administration of tartar-emetic and morphia. On January 1st, irritative fever, chills, profuse sweating, and vomiting set in, attended with haemorrhage and fœtid suppuration from the wound to the amount of four ounces. A compress and bandages were applied; stimulants and tonics administered. This hectic condition continued, with brief periods of amendment, till January 7th, 1863, when death occurred. The case is reported by Surgeon Thomas Antisell, U. S. V.

CASE.--Private Alfred McClay, Co. E, 114th Pennsylvania Volunteers, aged 17 years, was wounded at Fredericksburg, Virginia, December 13th, 1862, by a conoidal ball, which entered the right side at the costal cartilage, and emerged at the angle of the ninth rib, fracturing the rib between the point of entrance and exit. He was treated in the field, and, on December 17th, was sent to Harewood Hospital. When admitted, he suffered from traumatic pneumonia, which was treated by venesection and the administration of morphia and antimony. He recovered sufficiently to be able to move about the ward. The wound healed kindly. On January 11th, a profuse haemorrhage occurred from the wound, probably from intercostal artery, which continued in spite of compression. An unsuccessful attempt was made to ligate the artery. Tee haemorrhage was finally suppressed, after an alarming loss of blood, by tight bandaging and styptics. The stoppage of the haemorrhage was immediately followed by pain on both sides, cough, and expectoration. Pyaemia set in, and death occurred on January 24th, 1863. Necropsy: No opening had been made into the cavities, either by the missile or ulceration. Eight abscesses, from the size of a pea to that of an orange, were found in the lower lobe of the left lung, which was also in a very congested condition.

The case is made for or against venesection:

Haemothorax.--Sanguineous extravasation within the pleural cavity may result from lesions of the heart or arteries proceeding from it or veins emptying in it, or from wounds of the mammaries and intercostals, or from wounds or lacerations of the substance of the lung. It occurs at the moment of the wound or several days afterward, when the clots obstructing the divided vessels fall. It may rapidly fill the sac or slowly accumulate, varying in extent and rapidity according to the number and size of the vessels wounded. When rapid and profuse the patient perishes promptly from asphyxia, and hence the cause of many deaths on the battle-field.(5) When less copious, and gradually extravasated, it gives rise to a series of phenomena which awaken the surgeon's utmost solicitude. Dyspnœa may become excessive; the breathing is frequent and labored; there is urgent anxiety and oppression and agitation; the patient seeks to sit upright (orthopnœa) or can tolerate only a dorsal decubitus, or can rest only on the wounded side, or throws himself from one posture to another, drawing up the thighs, elevating the head and shoulders, in short, fighting for breath. He has a sense of great constriction and weight at the base of the chest. There is dulness on percussion, and the respiratory murmur is absent on the wounded side to the level of the effusion; the intercostal spaces are protuberant, the ribs are separated and raised, the hypochondriac region is prominent, the injured side moves but little in respiration. These physical signs are modified when air is present in the cavity; then there is tympanitic resonance above, and below absolute dulness. The undulations of the fluid are felt by the patient in sudden movements. The blood gushes out of the wound in coughing or violent expiration. Superadded to these signs are those of copious haemorrhage; the pulse becomesfrequent, small, irregular; the face is pallid, the lips livid; the extremities cold; vertigo, singing in the ears, and other premonitions of syncope supervene. In the presence of this formidable army of symptoms, the surgeon's first thought is to stanch the bleeding. If it proceeds from the heart or greater vessels, he can do nothing; but in lesions of the subclavians and carotids, and of the innominata even, he will compress, and if the haemorrhage can be temporarily controlled, he should apply ligatures. The mammaries and intercostals will be tied, if possible, and can always be controlled by compression. There remains for consideration only the bleeding from the lung tissue.

The application of cold to the chest, the administration of cold acidulated drinks, of opium, of digitalis, and acetate of lead, perhaps, may be of some utility; but the important point, on which much difference of opinion existed during the war, is whether the wound or wounds shall be kept open or closed. Until a comparatively recent period, no doubt was entertained that the surest mode of arresting the haemorrhage was to take blood from the arm. But, as will be seen farther on, this treatment is practically abandoned by American surgeons, and even those who still rely on venesection in inflammation, discountenance "preventive bleeding," or for haemorrhage.(1) The results of opening the wound and giving free egress to the blood, and of closing it and allowing the blood to accumulate and to arrest the bleeding by its own pressure, regardless of the danger of asphyxia, have been discussed on page 523. Probably this perplexing problem admits of no invariable solution. Chassaignac(2) proposed, in these cases, to encourage collapse of the lung, and thus arrest its bleeding, by injecting air into the pleural cavity; but I do not know that this theoretical suggestion has ever been acted on.

The reader will find some interesting observations on this subject in Dr. USHER PARSONS' Cases of Gunshot Wounds through the Thorax, with Remarks, printed in the seventh volume of the New England Journal of Medicine and Surgery, 1818, page 209. In relating the case of Captain Charles Gordon, wounded through the chest in a duel, Dr. Parsons says that he had been "subject to cough, and was threatened with a pulmonary affection, all which the bleeding from the wound appeared to remove. A similar instance is related to me by Dr. Wheaton, of Providence, in a case where a musket ball passed through the right lung of a young man labouring under phthisis pulmonalis. The haemorrhage was very profuse, but was followed by a speedy recovery both from the wound and phthisical affection. Query. Do not these facts speak in favor of venesection as a remedy in consumption as recommended by Dr. Gallup?"

Nervous Anxiety.--Great agitation, nervous anxiety, and general prostration sometimes follow the reception of wounds of the chest.(3) The alarm and apprehension accompanying this depression overcome the fortitude of men of the steadiest self-control and most devoted courage.(4) In analyzing this condition, the surgeon will endeavor to discriminate between the symptoms due to impeded respiration, those arising from faintness

(1) Of the effect of venesection in relieving dyspnœa, as practiced in some instances, in the France. Prussian war of 1870-71, Dr. H. FISCHER (Kriegschirurgische Erfahrungen, Erlangen, 1872, S. 126) remarks: "In cases of severe dyspnœa and cyanosis we practiced venesections. If not made too copiously the desired effect is reached; momentary relief of breathing and less oppressed circulation of blood, without depriving the patient of more blood than he needs for the approaching tedious suppuration. In several cases we observed excellent results, in other cases the effect of the venesection was very transient. In one instance we made repeated venesection, with only a very rapidly passing relief."

CSA discussion against venesection for chest wounds:

Dr. Chisolm (op. cit., p. 329) deprecates venesection in chest wounds, and gives an outline of the general treatment employed by the Confederate military surgeons:

"Where the heart and pulse are both weak--a common condition after severe wounds--in our experience the abstraction of blood will occasion a complete prostration of strength, and may be fatal. There is no reason for changing the plan of treatment already discussed in detail, for combating inflammation following gunshot wounds, and which is equally applicable to chest, wounds. Even when the lung is inflamed, we prefer the mild antiphlogistic and expectant treatment to the spoliative. The large success in the treatment of perforating chest wounds in the Confederate hospitals puts forth, in a strong light, the powers of nature to heal all wounds when least interfered with by meddlesome surgery. Absolute rest, cooling beverages, moderate nourishment, avoiding over stimulation, with small doses of tartar emetic, veratrum, or digitalis, the liberal use of opium, and attention to the intestinal secretions, will be required in all cases, and in most will compose the entire treatment."

Dr. Ashhurst(1) testifies that, in civil practice, he "has found no reason to adopt a different mode of treatment from that which has proved successful in the surgery of war." It may be regarded as generally admitted that venesection is unnecessary in penetrating wounds of the chest, and that it may be very harmful, and that the "draining of the system of blood," commended by Bell, Hennen, Guthrie, and Cooper, is to be numbered with the errors of the past.(

Antimonials.--Tartrate of antimony and potash(3) was employed to a limited extent to reduce the force of the circulation, and aid in the suppression of haemorrhage, and also to combat consecutive inflammations. But this remedy shared in the discredit into which venesection had fallen, and was little relied on by Union or Confederate surgeons..

Citations against use of vensection:

We are, however, by no means prepared to state that exceptional cases of plethora, in which such prophylactic venesection may be beneficial, do not occasionally occur; but they appear to be rare, and indeed are not likely to exist among soldiers on active field-service. Practical experience also, to which all theoretical opinions must give way, seems, during the late war, to point in this direction, and to do so independent of, and making allowance for, the cachectic state before alluded to, into which the bulk of the army had at one time fallen."

(2) LAWSON, G. (On Gunshot Wounds of the Thorax), gave his opinion that bleeding in these injuries is not called for as recommended by Guthrie Hennen, and the older army surgeons, and certainly was not applicable to the cases occurring in the Crimea.

(3) BLENKINS. Article--Gunshot Wounds, in the 8th edition of Cooper's Dictionary of Practical Surgery, London. 1861.

(4) MACLEOD, Notes on the Surgery of the War in the Crimea, Churchill, 1858, p. 237; GANT, The Science and Practice of Surgery, Churchill, 1871, p. 885. I say that Dr. Macleod's facts do not support his conclusions, because, though he reports eight recoveries in thirteen cases of shot wounds of the chest, it is not at all clear that the eight recoveries were complete, or that they were all from penetrating wounds, or that the bleedings practiced were of benefit, and because what he thought was generally observed, was denied by others, who had equal or greater opportunities for observation. Of fifty-one of the Crimean cases of chest wounds, carefully analyzed by Drs. Matthew and Fraser, free venesection was employed in seven,--in six of thirty fatal cases, and in one of twenty-one cases of recovery. How lamely Dr. Macleod's facts support his conclusions is illustrated by the cases reported by him on page 241, a fatal case of haemothorax without pneumonia, largely bled, and on page 247, "a soldier of the Buffs. He was largely bled, and his symptoms thereby relieved. Ten hours afterward a return of the difficulty of breathing called for further depletion and the use of antimony. Pneumonia followed" Mr. Gant's work has not been reprinted in this country, and it is unnecessary to examine the results of his experience at Scutari. The cases cited by Mr. HOLE (British Medical Journal, August 7, 1858) and Mr. MACKAY (Edinburgh Medical Journal, Vol. I, p. 924) in laudation of venesection, are their own best answer.

TREATMENT.--In the general management of wounds of the abdomen, venesection was abandoned, as far as can be learned, in the armies on either side, even more completely than in the treatment of wounds of the chest.(1)

1) Only four instances of blood-letting were observed in the returns, viz: Two cases in which venesection was practised: CASE 234, p. 76, and CASE 497, p. 155; and two cases of cupping: CASE 338, p. 139, and CASE 367, p. 13l. The old views on this subject are well known; they are expressed by THOMPSON (J.) (Report of Obs.. etc,, after Waterloo, 1816, p 106) : "It cannot be too frequently repeated that copious blood-letting and the use of the antiphlogistic regimen, in all its parts are the best auxiliaries which the surgeon can employ in the care of all injuries of the viscera contained within the cavity of the abdomen." But forty years later, in the Crimean War, it was discerned by the British surgeons, at least, that the antiphlogistic treatment formerly in vogue was no longer applicable Thus, MATTHEW (Med. and Surg. Hist., etc., p. 329) observed: "In none of these cases does general blood-letting appear to have been indicated, and it was employed in very few instances." After the Austro-Prnssian War of 1866, NEUDORFER wrote (Handbuch der Kriegtchirurgie, 1867, S. 731) : "As regards blood-letting, the majority of the later French surgeons, as well as some of the Germans, who cannot shake off the fetters of the older French tradition, still cling to venesection; but the majority of German and American and English surgeons, formerly staunch supporters of venesection, have now abandoned it."

Cases citing use of venesection:

CASE 15.--Private George Kellers, Co. B, 5th Mich., was admitted Nov. 7, 1861, having had acute bronchitis with high fever for twelve days prior to admission: Pulse 106; face flushed; respiration 32; tongue dry and brown in centre; cough frequent; uneasiness in lower part of the chest, amounting to dull pain on full inspiration; viscid and bloody sputa. Applied blister and gave Dover's powder eight grains, calomel one grain. 8th: Pulse 120, quick; respiration 32; tongue dry and brown; skin hot; countenance anxious; expectoration scanty, viscid and slightly tinged with blood; lips blue and nostrils dilated on inspiration. Gave small doses of quinine, calomel, turpentine and chlorate of potash, whiskey occasionally and milk as desired; applied dry cups to back. In the evening gave veratrum viride and ipecacuanha. 9th: Pulse 106, feeble; respiration 44, labored; lips dark-purple; countenance anxious; nostrils widely distended on inspiration; thick mucous expectoration. Applied dry cups to back; gave brandy; half a grain of calomel every hour; dressed blister with mercurial ointment. 10th: Pulse 84, full and soft; respiration 43, short; no respiratory murmur in right lung; dulness with but little expansion. Continued calomel and stimulants. 11th: Pulse 84; dyspnœa urgent, somewhat relieved by the removal of ten ounces of blood by vene-section. 12th: Dyspnœa increased. Gave quinine eight grains daily; brandy punch. Removed a few ounces of blood by venesection. 16th: Some expectoration; respiration 30; countenance less anxious; tongue cleaning; pulse 120, soft. 17th: Pulse 120; respiration 32; tongue clean; free purulent expectoration. 2 P.M.: Much pain in right side; great dyspnea and much anxiety of countenance; profuse sweating. 18th: Died.--Hospital, Alexandria, Va.

Surgeon M. R. GAGE, 25th Wis., Dec. 31, 1862.--Since that period [early in December, 1862] cases of congestion of the lungs have been quite numerous, but under the following plan of treatment have been mostly brought to a successful issue. First, the administration of tartar emetic ad nauseam, giving the remedy every one, two or three hours, according to the urgency of the symptoms, and making thorough counter-irritation to the thoracic region. Free catharsis is induced by podophyllin and calomel in those cases in which the tartar emetic does not itself sufficiently act upon the bowels for depletory and revulsive purposes. One case of congestion of the lungs proved fatal while on the march across the bleak prairies from Mankati to Maiona in severely cold weather. I did not see the case; but am informed that the patient was almost at once overwhelmed, the attack proving fatal in a few hours. Doubtless venesection might have been in this instance very properly practiced, but whether or not successfully of course cannot be said. Veratrum viride is sometimes made use of, but I think does not act with that promptness and efficiency which long experience has shown to result from the administration of tartar emetic

Surgeon M. R. GAGE, 25th Wis., March 31, 1863.--In most cases this disease is ushered in by slight or severe chills, soon followed by increased heat of surface and severe febrile symptoms. There will also be found often pain in the loins and a stitch in one or both sides of the chest, accompanied with cough, and in many cases dyspnoea and great pectoral oppression. In the beginning the cough will be dry and harsh, but there soon appears a frothy mucous expectoration, which becomes in a short time the rust-colored sputa so characteristic of this complaint. A full and bounding pulse shows the excited state of the circulation. If the case be ushered in with symptoms of great severity venesection is promptly resorted to and is, we believe, the only reliable means of arresting or controlling the disease. The bleeding should not be stinted but liberal; a large opening should be made in the vein and a full, free stream allowed to flow until syncope is established. This course, it must be understood, is applicable only to those who are healthy and plethoric, and when the onset of the affection threatens imminent peril to the integrity of the organs attacked. In the case of a feeble constitution, or when the pulmonary organs are already affected by tuberculosis, there would be doubt as to the propriety of bloodletting, or, if decided Upon, a manifest impropriety in carrying it to the extent just indicated. After the bleeding tartar emetic is administered ad nauseam; cathartics may also be brought into requisition, and are invaluable adjuncts in pursuing the treatment already shadowed forth: Dover's powder, ipecacuanha and calomel, in alterative doses, are of the first importance in assisting the efforts of nature to clear the affected lung from the inflammatory products deposited in the air-cells. Cupping over the pectoral region may be <ms_p3v1_809>employed in the early stages to good advantage; benefit may also be derived from the application of sinapisms and at a later period from blisters. The patient toward the end of the attack may require a supporting course, such as beef-tea, wine, quinine, etc. [During the quarter ending March 31, 1863, Surgeon GAGE treated in his regimental hospital eighty-eight cases of pneumonia, six of which terminated fatally.]

Article on anesthesia during the Civil War

Article on ligation of an artery during the Civil War

Article on suturing during the Civil War

Article on chloroform during the Civil War

Article on how an amputation was done during the Civil War

Additional information on the Chisolm ether and chloroform inhaler