Samuel Henry Dickson, M.D.

Click on image to enlarge

Samuel Henry Dickson, M. D., was born in Charleston, S. C., 1797. After graduating in Yale College, and then in medicine at University of Pennsylvania, he practiced his profession many years in his native city, and established the Medical College there. In 1847 he was Professor in University of New York, and after the war (having returned South and lost everything in the contest) he accepted a chair in Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, which he filled until his death a few years ago. His published volumes have been on medicine or collateral subjects, except Essays on Slavery, 1845. He is said to have delivered the first temperance lecture south of Mason and Dixon's line. His essays on literary and scientific subjects have been numerous, and his occasional verses are remarkable for simple grace and true feeling.

_______________

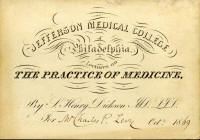

Samuel Henry Dickson, M.D., LL.D., who died in Philadelphia, March 3ist, in the 74th year of his age, had been for nearly fifty years'a medical professor. He was born in Charleston, S.-C., Sept. 20, 1798, graduated from Yale College in 1814, studied Medicine in Charleston, and practised there during the terrible epidemic of yellow fever in 1817, subsequently prosecuted his studies in Philadelphia, and took his medical degree there in 1819. In 1823, he commenced lecturing before the physicians and medical students of Charleston on physiology and pathology ; in 1824, was called to the Chair of Institutes and Practice of Medicine in the New Medical College there, which he had helped to found. In 1832 he resigned, but on the reorganization of the College in 1833 he was reflected and continued there till 1847, when he was called to the Chair of Practice of Medicine in the University of the City of New York, but in 1850 his health obliged his return to his former post. There he remained till 1858, when he was called to the Chair of Practice of Medicine in the Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, where he continued to lecture until his de,ath. Dr. Dickson was the author of several medical and other works, which indicate talent of a high order.

_________________

Professor Samuel Henry Dickson, M.D., LL.D., was born in Charleston, S. C., September 20, 1798, and died in Philadelphia, March 31,1872. In 1811 he entered the Sophomore Class at Yale College, and graduated in 1814, at the early age of sixteen. He commenced the study of medicine during the same year, in the office of Dr. P. G. Prioleau, a distinguished physician of his native city, remaining with him for five years. He attended two courses of medical lectures at the University of Pennsylvania, fi om which he graduated in 1819. His practice began the July following his graduation, and soon became one of the most extensive and most lucrative in this country, and continued so until ill-health forced him to retire from its active duties.

In 1822 he read a course of lectures on physiology to a class of young men, and in 1824 took the chair of Professor of Institutes and Practice in the Medical College of South Carolina, of which he was one of the founders. This position he afterwards resigned, but soon, in conjunction with other medical gentlemen of distinction, established another College in Charleston, in whieh he occupied a similar chair. Here he remained until 1847, when hu accepted an invitation from ihe University of New York to fill the same position in that institution. He always referred witii pb asure to this portion of his life, as his reception by 1rs colleagues, and his intercourse with them and with the profess:on generally, as well as the literary and soc:al circles of New York City, was most cordial and agreeable. He remained in New York for three winters, when he was urgently invited to return to the position he had filled in the Charleston College, to accomplish which Dr. Bellinger, the Professor of Surgery, resigned his chair to Dr. Geddings, who had taken Dr. Dickson's professorship on the letter's removal to New York. When Prof. Dickson returned to Charleston, he was most warmly welcomed, a public dinner having been given him by his friends in the profession and nut of it. He remained in Charleston until 1858, when he accepted an invitation to join the faculty of Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia, the death of his special friend, Dr. J. K. Mitchell, having left the professorship of the practice of medicine vacant in that institution ; and here he lectured until death called him from the duties he loved so well.

From early life Prof. Dickson had suffered ill-health; from 1825 being ill with phthisis, attended with many hemorrhages from the lungs, and in 1857 being first attacked with the painful malady of which he eventually died. He had been invited to the medical colleges of Lexington, Ky., Augusta, Ga., Richmond, Va., and Nashville, Tenn. His contributions to medical journals have been absolutely enormous, and the habit of writing was continued almost to the last days of his life. His bes' known and largest work is his Practice of Medicine, fi st published in two volumes, and afterwards condensed into one. It was a masterly production, and at once commanded attention and respect. In the earlier editions of this work will be found many physiological and pathological opinions upon disease, which, at the present day, are considered progressive, but which his acumen detected a score of years in advance of the regular progress of medical science. His work on Dengue, his Essayt on Life, Sleep, Pain and Death, and his Studies in Pathology and Therapeuiics have also been vегу widely read, and greatly appreciated ; but besides these productions, there have been hosts of paper?, not only on subjects purely medical, but upon almost every conceivable topic that could interest a reader and man of science—papers which it would be impossible to enumerate in the limited space at our disposal.

Prof. Dickson was one of the most scientific ami well- read men that our profession could boast of. His familiarity with ihe classics, with the elegant literature of the past century, and the new topics of his own time was wonderful. He was a lover of the historian and of the muse, and often brought their records and their ihy me to bear upon the illustration of the subjects of his lectures, or topics of conversation. He loved the good writers of fiction also; and Dickens and others were occasionally mentioned in his lecture-room as having depicted some of tlie objective symptoms of certain lingering diseases more minutely and picturesquely than some of i he masters of medical literature.

Prof. Dickson, at least during the later уеaгs of his life, did not resort to diagrams, models, or specimens in his lectures; but he strongly encouraged post-mortem investigations, and bed-side observation. His style of lecturing was somewhat peculiar. He spoke extemporaneously, without note or paper, but occasionally he would read an extract from a book that had engaged his attention while preparing for the lecture. He entered the lecture-room dressed as he came from the street, hat in hand; and, bowing to his class as he placed his hat on the desk and deposited his gloves, commenced in a colloquial way, which seemed to say of itself—аз well as manners can speak—" I was passing by, gentlemen, and thought I would drop in and talk to you this morning about—so and sо."