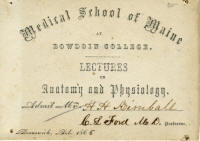

Corydon L. Ford, M.D.

Click on image to enlarge

Name: Corydon L. Ford

Cause of death: apoplexy

Death date: Apr 14, 1894

Place of death: Ann Arbor, MI

Birth date: Aug 29, 1813

Place of birth: Lexington, NY

Type of practice: Allopath

Medical school(s): Geneva Medical College, Geneva: Syracuse University College of Medicine, (G)

Journal of the American Medical Association Citation: 22:601Corydon L. Ford, that gifted teacher of anatomy, is no more. He finished his one hundred and ninth course of lectures on April 4, 1894, the same date that his life-work and his life with us ended. Born and reared in some little unknown village in the State of New York, the beginning of his life was as obscure and common-place as that of Abraham Lincoln, whom he resembled in some of his rugged, strongly-marked and picturesque features. The impression at this time is that lie obtained his education at the public school, and may have had some aid in a higher grade of study, but he never had a collegiate training. At an early age he taught in a public school, but only for a short time, and then entered upon the study of medicine. With but little preliminary training he made great progress by his own gifts, energy, perseverance and Iteroie effort?. As soon as he graduated he began to teach anatomy in some subordinate position, and in a little while rose above his associates and took first place.

"The greatest teacher of anatomy," he has often been called, and I believe he was the greatest that this world ever saw. To live, to act, to die as this man did is as full and complete a record as the human heart desires. Men there may have been who knew more about general anatomy; some made more discoveries in this branch of science, but^few, if any, equaled him in his knowledge of human anatomy, and none came near to him as a teacher. Ford stood alone, far above all others, in his capacity.as professor of anatomy, gifted far beyond compare with that rare power to impart knowledge. lie was ever on a higher plane than his contemporaries. He took this position, too, in spite of many disadvantages. As already stated, his early education was far from being as complete and comprehensive as is now deemed necessary to fit a man for the profession of medicine, yet he did preeminently that for which many Americans have been noted, namely, superb scientific professional work without a full preliminary training. He began to teach anatomy early in life, and without a break lie continued his work for nearly sixty years. A slight physical defect (the only one in his whole being) made him lame; this disqualified him for the practice of mi-dicine and surgery to any great extent, but happily anchored him to the study of science and teaching. This no doubt had much to do with determining his course of life and in making his career, now closed, so thorough and well rounded out. This weakness of one limb was far more than compensated for by extraordinary health and strength, mental and physical.

His knowledge of anatomy was most extraordinary and was gained at first with a little help from books and teachers, and then all the rest was obtained by his study of nature. He did not go to the library to investigate or refresh his memory, but to the living structures in the woods, fields, highways and byways, and to practical investigations in the laboratory of practical anatomy. He was a pioneer in this method of study, for I believe he preceded Agassiz who founded the great school of practical observation and study of zoology from nature. He was also a pioneer in his teaching by object lessons and demonstration. His knowledge of the great principles of his subject was most thorough, and in every detail complete and familiar as the alphabet of his mother tongue; so much so that he was able to accurately express himself without effort or hesitation. He was in this respect like the choir of the forest whose heads and hearts are full, and overflow in melodious song.

His knowledge and love of anatomy and his enthusiasm, which never slumbered, were the basis of his strength. His method of teaching, the Socratic, was by raising questions and answering them. This method he matured to the highest degree. His ability to excite interest in students and keep them interested was wonderful. Anatomy was the " pons asinorum" of medical students until Ford made it as fascinating as poetry or fiction. So plain, simple and interesting were his lectures that a layman who knew nothing of the great science of organization would listen to him by the hour with pleasure and profit.

Not being engaged in the actual practice of medicine or surgery one would naturally expect that his teaching would have been impractical, that lie would deal more with the science of anatomy than with its practical utility, but here he surprised every one who ever listened to him by teaching physiology and surgical anatomy most impressively. A few words regarding what any structure that he had described was " good for," very briefly but fully taught physiology, and in his descriptive anatomy he invariably added to the interest of his demonstrations by showing how convenient it was for the operator to know about the relation of things. " What is it good for? " " What is the use of it? " were questions which he continually raised, and answered them briefly, practically, and in a way never to be forgotten by the physiologist or surgeon. He would often say, " You may have occasion while operating to look for this artery, here it is; what is in front of it? look and see, here it is. What is behind it? on the right of it? on the left of it?" To each question came the answer, "You can see it right there."

Thirty years ago I attended his lectures and demonstrations, and many of the practical and useful things in anatomy then presented remain as clearly in mind to-day as when they were at first impressed. I have heard him lecture daily for months without hesitating a moment for the plainest and most effective of words to express bis ideas, and without once using the personal pronoun, I. He was not only, then, the greatest teacher of descriptive anatomy, but of surgical anatomy, and of physiology; and this was done without any apparent effort. It may be truly said that one learned anatomy from Ford without the consciousness of being taught. Anatomical lectures and anatomy as a study have always been considered dry, difficult and uninteresting, and the great majority of students dread them, and are glad to be through with them.

As a man, Professor Ford was clear-headed, kind-hearted,'pure-minded. He lived a life of seclusion, knowing nothing of the so-called pleasures of life. It is doubtful if he was ever in a place of amusement during his life, but he was quite entertained in his work with his students, associates and friends in college. Plain, simple and severely correct in all his habits, his wants were easily supplied, and by setting a limit to his desires he was able to gratify them all with little means. While Professor Goodsir was receiving ten or fifteen thousand dollars for teaching anatomy in Europe, Professor Ford in this country was receiving little more than fifteen hundred^ Strange it is that in this country the people will give thousands of dollars to a prima donna for singing a song while college professors labor for the wages of a ploughman. It is more wonderful that men like Ford can be found who love science, learning and humanity enough to serve without gold.

He gained the respect of everyone who came in contact with him, and this respect grew to profound admiration. He associated always and intimately with students, and the nearer they came to him the more they felt his strength and goodness. There was no cold atmosphere of assumed dignity put on to conceal weakness. He was pure, manly and strong enough to be always transparent while with his students, so that the more they knew of him the more they found to admire, and the surer they felt that there was no weakness that he had to conceal. The wildest boys in his class became gentle and respectful, quiet and attentive, the moment he looked at them. He was the gentle shepherd that led his flock with tender care. He was unassuming, retiring, gentle—almost timid—and in his manner, in this respect, he seemed to possess the disposition of the refined woman, yet withal he was one of the bravest men that one could meet. In the session of 1861-2, his associate, Professor Gunn, that remarkable surgeon, was serving the country as a military surgeon, and Professor Ford in addition to his lectures on anatomy took up the work of his absent associate, and then we had occasion to see him operate, and this he did with an accuracy and firmness of touch which led one to believe he was wholly unconscious of the term " nervous " as commonly used. One of his students, at the time, who had a fancy for surgery, but was fearful that he would not be able to practice that branch of medicine because of his tender-heartedness, learned from Ford that the tender are the bravest. This student had the impression, which was popular then, and is probably so at the present time, that a surgeon must be hard-hearted and unfeeling in order to be able to do major surgical operations; but an incident in the life of Ford taught him the truth on this subject. A few days after seeing the professor calmly and coolly do a very important operation in the amphitheater, the student had occasion to sit beside him at a public meeting where the speaker told an exceedingly interesting but pathetic story,, and at the conclusion of the narrative when he turned to look at the master he found that ideal anatomist and surgeon with tears flowing as freely as they ever did from the eyes of the most affectionate mother or maid.

I have an idea also that he was a man of profound religious feeling. I kiiow lot and care not what his creed was, but he impressed me as a man who adored he good, the right, the true, omnipotent and benevolent; that the Being with these attributes was tlie God that lie worshiped and the diety whom he saw through his works and whom lie aimed to serve in all things. Solid as a rock which long resists the elements, he remained young far into the afternoon of life. At three-score and ten as active as at forty, with abundant hair, without a silver thread noticeable in it; when nearing four-score' there was a little more repose, a little less fire in his lecture, more time in the easy chair after the chief work of the day was done, less time in the museum and laboratory, but no signs of decline such as are usually visible in the aged. The night came to him, as it comes in his own country, after a very brief twilight.

The influence which Professor Ford exerted upon the profession of this age can be thought of but cannot lie computed: He was not the physician and surgeon who serves his fellow-men in a way which brings admiration and endless loving memories of his goodness and value. Works of such good men are seen and appreciated, and when they have finished their life-work we can estimate them by comparison with other great men in the profession who have come and gone; but I contend that the influence for good exercised by Professor Ford in his long career was as great, or greater than any in the profession, although unseen by the vast majority of mankind. He taught anatomy when there was so little time for it that there would have been but few anatomists sufficiently qualified in this branch of medicine to be either good physicians or surgeons. He taught more and in less time than any other man could do. How many physicians and surgeons are there in this and other countries who owe their success to the grand work done for them by Ford? He certainly laid the foundation upon which it was possible to build an education which could secure success. He robbed anatomy of all that was unattractive or repugnant in the study, and made it a living, pure, attractive and useful knowledge.

Another way in which he rendered the profession a service which should keep his memory ever present and ever young was, that he made teachers of other men. Many of those who are teaching the various branches of medicine to-day owe much of their success to the fact that he, unconsciously, perhaps, on his part or the part of his students, taught them how to teach others. On one occasion he complimented a young teacher (who had been his pupil) upon his success. The youthful doctor thanked his old master and added, "It comes naturally; I have the teaching diathesis, caught from Professor Ford when I was a boy." He did much to make good, honest, faithful men; he excited interest and induced students to study, and to study thoroughly and faithfully, and imparted to others the power to teach, to a degree that few if any have equaled; <ind altogether his influence on the profession in America is perhaps greater

and more lasting than that of any who went before him to the " pule realms." In looking back to early days, the pleasantest and most profitable in one's student'* life began while with Ford, and the impressions then made stand out as a guiding star and beacon light, shining even now and telling that his influence still lives and will live after him.—A. J. C. Skene, M. D., in The Brooklyn Medical Journal.______________

Moses Gunn was elected dean for the 1858-1859 academic year. Gunn was born in New York in 1822, and in 1844 he attended the Geneva Medical College in New York. There he was mentored by Professor of Anatomy Corydon L. Ford, who eventually succeeded him as dean at Michigan. Ford remained at Geneva to teach, but the ambitious young Gunn left for Ann Arbor after graduating in 1846. Just prior to his departure, Geneva College received a cadaver, an unclaimed body from the Auburn State Prison. Since it arrived too late to be used in class, the body was given to Gunn for teaching purposes. He brought the cadaver with him to Ann Arbor and performed a dissection in front of guests. This was the first such demonstration in Ann Arbor, and possibly all of Michigan. His series of lectures were so well attended and successful that in the fall of 1846 Gunn taught anatomy at a private medical school in Ann Arbor. Gunn and Silas Douglas started the school while waiting for a Medical Department to be created at the University of Michigan.

After the regents made their decision to found the Medical Department, Gunn was appointed as the third faculty member at the University of Michigan. At Pitcher’s recommendation, he was made professor of anatomy and surgery in 1849 at age 27. Gunn’s research at Michigan included an investigation of which particular tissues cause hip and shoulder joint dislocations. He worked on a method of guiding these dislocated parts back into position by gently directing the bone back through its course of escape from the socket. Gunn’s results were published in the Peninsular Medical Journal.

Though Gunn initiated a tradition of excellent anatomy instruction at Michigan, he was also interested in surgery. A capable, determined man, Gunn became professor of surgery in 1854, holding the title until 1867, when it was taken over by his long time friend and colleague Corydon Ford. Gunn served as a surgeon for 11 months in the Civil War, seeing active duty during General McClellan’s peninsular campaign. Gunn resigned from the University in 1867 after the sudden death of his son by drowning, and moved to Chicago with his family. There he became chair of surgery at Rush Medical College until he died in 1887. C.B.G. de Nancrede wrote of Dr. Gunn that:

Altogether he presented an impressive figure of a man of physical and mental power, of one who must investigate everything presented to his senses, who quickly observed, classified his impressions, deciding upon the respective merits and proper relation even of passing events, a man of an alert and enthusiastic temperament, ready and eager to digest new ideas, yet one whose judgment restrained his zeal within due bounds… A man thus opulently endowed by nature and trained by a life of continuous effort to excel, could not fail to command at the very outset the attention and confidence of any audience, and to exert an actively compelling influence over them. [Nancrede, C.B.G. de. “Moses Gunn, A.M., M.D., LL.D.” Michigan Alumnus 12 (1905-06): 364-374].

Gunn’s friendship with Corydon L. Ford proved to be an asset for the University. Like Gunn, Ford earned such respect and distinction in the Department that he was elected dean in 1861, and returned to the post from 1879-1880 and 1887-1891. Ford earned his M.D. from the Geneva Medical College in 1842, where he then taught anatomy from 1842-1848. He came from a family of farmers, but paralysis of one leg as a child made it impossible for him to pursue this vocation. He used a cane the rest of his life, and had he not been dealt this setback, he most likely would have followed his family’s line of work in farming. This would have, as Alonzo Palmer wrote in 1886, deprived “the profession of medicine and the science of anatomy in this country of what many have reason to believe its most successful teacher.” Ford began teaching at the age of 17, and in 1834 he started studying medicine in the office of Dr. A.B. Brown of Niagara County, New York. It has been said that Ford’s disability and illness caused him to view the darker side of life, but he was nonetheless compassionate, approachable, and kind.

Ford was greatly respected and admired by his students and colleagues. By the time he was appointed to the chair of anatomy at the University of Michigan in 1854, he was known as an excellent teacher at several institutions. He was described as “an eloquent teacher, able to infuse life within dry bones.” Considered a great lecturer and demonstrator, he was one of the students’ favorite teachers. He had a high skill in dissecting, an ability to make a clear and concise presentation of the material, and an enthusiastic demeanor. Dr. William Mayo, a Michigan alumnus and student of Dr. Ford, said

By his forceful personality and his intense love of his subject he made the too often dull study of general anatomy as interesting as a novel. Contrary to custom, Ford preferred to make his own dissections while he talked, and he did them beautifully and rapidly. When he had finished one he would swivel the table around toward the class with a flourish, pointing upward with his cane to emphasize his words, “Now gentlemen, forget that—if you can.” (Clapsattle, Helen: “The Doctors Mayo,” Atlantic Monthly 68:645-47, 1941)

Aside from teaching, Ford wrote several significant works including “Questions on Anatomy, Histology, and Physiology, for the Use of Students” (last ed. Ann Arbor, 1878), “Syllabus of Lectures on Odontology, Human and Comparative (1884), and “Questions on the Structure and Development of the Human Teeth” (1885). Dr. Ford was given a LL.D. from Michigan in 1881. After giving his last lecture in 1894, he turned wearily to an assistant and said, “My work is done.” He collapsed on his way home, and died the next morning.