An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy

From: Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Penn.

Joseph Leidy (1823-1891): Encyclopedist of the Natural World

When Joseph Leidy started his career in 1845, scientific research was dominated by gentlemen amateurs and wealthy collectors. By the end of his life, science in the United States had become increasingly professionalized and specialized. Leidy straddled these two worlds. He was an acclaimed researcher, but his income came primarily from teaching and an assortment of administrative duties. Unlike the specialized scientists of the late 19th Century, however, he had expertise in and made significant contributions to a wide range of subjects. To borrow the apt subtitle of Leonard Warren's recent biography (1), Leidy was "the last man who knew everything."

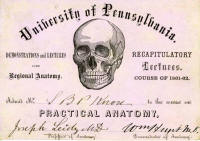

Joseph Leidy published An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy in 1861 following years of frustration with the lack of a clear and usable textbook on human anatomy. His book was widely acclaimed by critics and adopted by American medical students and physicians for several generations. This book helped establish Leidy as the foremost American anatomist of the age.

The book was 663 pages long and contained a total of 397 illustrations. (Many of the illustrations were drawn by Leidy himself.) Leidy created a book that could be used as a dissection manual as well as a textbook. Students could take it into the lab to guide them as they examined cadavers.

This book wasn't a radical departure from earlier textbooks. Instead, it contained updated information and a number of improvements. Perhaps the most significant improvement was its clarity. One of the most serious shortcomings of earlier textbooks was the confusing jumble of technical names. Leidy responded by using English names whenever possible and writing concise and clear text. He is reported to have tested its clarity by reading the manuscript aloud while a colleague identified the corresponding parts and tissues while examining a cadaver.

Leidy discussed the fundamental qualities of living matter in the introduction to his book. He stated that all living bodies were the products of their parents and that he knew of no evidence that had ever demonstrated spontaneous generation. He goes on to say that living matter derives its substance from the mineral world. As such, he argues, it's subject to the same physical laws. He then discusses the chemical composition of the body and the different types of tissues. As with many of his other writings, Leidy advocated the microscope and a vital tool.

The introduction continues with Leidy's endorsement of Darwin's theory of Natural Selection. He emphaizes that life has existed for "incalculable ages" and that "this process of the successive origin and extinction of races or series of species has continued without interruption down to the present period."

A completely revised and expanded second edition of An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy was completed in 1889, two years before Leidy's death. The discussions on the nature of living matter, spontaneous generation and evolution were not included in this edition, presumably because these ideas were already widely adopted by his readers.

Classic texts -- in the flesh by Jason Schwartz: The Daily Pennsylvanian

In the 19th century, Penn faculty were known to bind books with human skin, and Van Pelt still displays an example of the macabre craft.

They say not to judge a book by its cover, but that can be difficult when the cover is made of human skin.

Residing on the sixth floor of Van Pelt Library, Bibliotheque Nationale, a catalogue of medical texts published in 1857, is bound in human leather tanned by 1868 Penn Medical School graduate John Stockton Hough.

Though Van Pelt is just one of many prominent libraries on the East Coast -- including Harvard and Brown universities' -- to own a book bound in human leather, the University has an especially strong link to the tanning of human skin.

Though an effort was made to keep this practice from becoming widely known, it was relatively commonplace in the latter half of the nineteenth century, according to a St. Louis Post-Dispatch article from the era tucked between the cover pages of Bibliotheque Nationale.

Because most of those who bound their books in human skin were physicians and Penn had a leading medical school at the time, many human-skin tanners were Penn graduates, according to Laura Hartman. Hartman is a rare-book cataloger at the National Library of Medicine in Maryland and an expert on anthropodermic binding (the slightly more palatable term for human-skin binding).

The tanning was often done in the now-defunct Philadelphia General Hospital, once located at the current site of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, just a few blocks off campus.

"There were certainly some Penn-affiliated physicians tanning human leather in the [hospital] basement," Hartman said.

Joseph Leidy, for whom the Leidy Laboratories of Biology are named, was a professor of anatomy at Penn for over 40 years. He had his seminal work, An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy, bound in skin from a soldier who died in the Civil War.

According to Hartman, Leidy was a physician for the Union during the Civil War and the skin likely came from one of his patients.