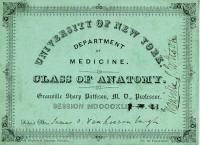

Granville

Sharp Pattison, M.D

Click image to enlarge

Go to lecture card display

Granville Sharp Pattison died in

the city of New York, November 12th, 1851, in the sixtieth year of his

age, after having occupied for nearly two-thirds of his life a

conspicuous place in the public eye. It is no exaggeration to say that

no anatomical teacher of his day, either in Europe or in this country,

enjoyed a higher reputation. There were undoubtedly many anatomists far

more profoundly versed in the secrets of the human frame, more

dexterous, patient, and minute dissectors, and men better acquainted

with the use of the microscope, or the study of the tissues, a branch of

anatomy now known as histology. Indeed, it is not too much to assert

that if he was not ignorant of histology and microscopical anatomy his

knowledge was very superficial. It may, however, be said that these

studies were, even at the time of his death, in their embryonic

condition. Only glimmerings of light had as yet broken in upon the

profession. Granville Sharp Pattison died in

the city of New York, November 12th, 1851, in the sixtieth year of his

age, after having occupied for nearly two-thirds of his life a

conspicuous place in the public eye. It is no exaggeration to say that

no anatomical teacher of his day, either in Europe or in this country,

enjoyed a higher reputation. There were undoubtedly many anatomists far

more profoundly versed in the secrets of the human frame, more

dexterous, patient, and minute dissectors, and men better acquainted

with the use of the microscope, or the study of the tissues, a branch of

anatomy now known as histology. Indeed, it is not too much to assert

that if he was not ignorant of histology and microscopical anatomy his

knowledge was very superficial. It may, however, be said that these

studies were, even at the time of his death, in their embryonic

condition. Only glimmerings of light had as yet broken in upon the

profession.

Pattison's forte as a teacher

consisted in his knowledge of visceral and surgical anatomy, and in the

application of this knowledge to the diagnosis and treatment of diseases

and of accidents, and to operations. He had studied surgical anatomy

under Allan Burns of Glasgow, its founder in Great Britain, and I may

add in this country, where the republication of his work, entitled The

Surgical Anatomy of the Head and Neck, awakened unexampled interest and

enthusiasm in this department of science. His great charm in the

lecture-room was the earnestness of his manner and the clearness of his

demonstrations. He would throw his whole soul into his subject, and use

every exertion to make himself felt and understood; and his enthusiasm

never failed to infuse itself into the dullest pupil. The appointed hour

always seemed too short, so rapidly and pleasantly did it pass. What

added interest to the speaker was a slight lisp and a Scotch accent,

which never entirely forsook him, despite his efforts to overcome them

in early life. Pattison never indulged in any of those physical displays

occasionally witnessed in our amphitheatres. On the contrary, he was

dignified, entertaining, and instructive. He possessed that peculiar

kind of eloquence which is so well calculated to enchain the attention

and enlighten the mind of the medical student—an eloquence difficult to

describe, but without which no teaching can be attractive or make an

abiding impression upon one's auditors.

It was my lot to be associated with Granville Sharp Pattison during the

session of 1850-51 in the New York University, in which I served as

Professor of Surgery as the successor of Valentine Mott . One morning,

in the summer previous to the session, during my residence at

Louisville, a telegram was handed to me at the breakfast-table, in which

I was asked whether I should be at home on a certain day the following

week, the writer adding that he desired an interview with me. When the

appointed time arrived I was not a little surprised to see before me a

small, elderly gentleman, of medium stature, with black eyes and white

hair, who introduced himself as Mr. Pattison. Up to this time I had

known him only by reputation. He soon explained the object of his visit.

He painted the prospects of the University of New York in the most

glowing colors, spoke of his colleagues as though they were the greatest

and most learned of professors, and peopled the amphitheatre at no

distant period with from eight hundred to one thousand students. I shall

never forget his enthusiasm. I was then in a halting frame of mind, for

the University of Louisville was in danger of passing out of the hands

of its trustees into the management of a board to be elected annually by

the City Council, by which the school had been largely endowed. The

question propounded to me required time for reflection. Pattison left

the next morning, depositing with me a guarantee of four thousand

dollars for my winter's labors in the event of my acceptance. At the end

of a week I sent an affirmative answer. The history of my connection,

however, with the University of New York, and of my return to

Louisville, is related elsewhere.

At an early period of his professional life he edited an edition of

Allan Burns's Surgical Anatomy of the Head and Neck and performed

several important surgical operations, tying, it is said, upon one

occasion, the omohyoid muscle instead of the common carotid artery. But

his surgical tastes, if he ever had any, never grew upon him, and as he

advanced in years the sight of blood became distressing to him.

The career of Pattison was a checkered one. He was born near Glasgow,

where, at the age of seventeen, he began the study of medicine. At

twenty-one he became an assistant of Allan Burns, and devoted himself to

the study and teaching of anatomy. From Glasgow he came in 1818 to

Philadelphia, under a promise of the chair of Anatomy in the University

of Pennsylvania, then recently vacated by the death of Dr. Dorsey, a

nephew of Dr. Physick.

A cloud, however, followed him to

this country, and he was accordingly tabooed upon his arrival. He

subsequently engaged in a duel, in which he shot his adversary in the

hip, laming him for life. Despite this adventure, he was soon after

appointed to the chair of Anatomy in the University of Maryland, which,

in consequence of his brilliant teaching, speedily attained a high

degree of prosperity. In 1828, upon the organization of the now

celebrated London University, he was called to the chair of Anatomy. A

serious misunderstanding soon arose between him and the Demonstrator of

Anatomy, Dr. Bennett, and he left London in disgust. He returned to

Philadelphia, and served as professor of his favorite branch in the

Jefferson Medical College from 1831 until 1840, when he assisted in

founding the Medical Department of the University of the City of New

York. Like a rolling stone, Pattison gathered no moss, and consequently

left no estate, although his "dear Mary," having means of her own, was

comparatively comfortable after his death.

|