6th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia

Pratt Street Riot in Baltimore

Norman Smith, M.D.

Information and notes related to Dr. Norman Smith, Surgeon, 6th Militia

An earlier and later image of Norman Smith, M.D.

Documentation of the amputation performed by Norman Smith, M.D. in Washington, D.C. after the Baltimore Riot

Moses S Herrick Dr. Norman Smith's amputation patient 1861

Documentation regarding the uniform worn by Dr. Smith in the document photos

Norman Smith's Colt Dragoon pistol

Additional information on Dr. Norman Smith in his uniform

Return to the display of the Norman Smith surgical set

Documentation regarding the uniform worn by Dr. Smith in the photos

6th Mass. Vol. Militia and the Pratt Street (Baltimore) Riot at the start of the Civil War

For a 'historically accurate version of the Baltimore Pratt Street Riot, please read the pages of the 1917 book by James Ford Rhodes: (photos of Rhodes text courtesy of researcher and author Larry DeCan)

The first (Civil War) 6th Regiment Infantry, Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (3 months tour) was mustered into Federal service on June 22, 1861. This Regiment was know as the "Old Sixth", referring to the unit's organization in Revolutionary War times. They had gone through the Baltimore Riot on April 19, 1861, as Massachusetts Militia. The unit was mustered out of Federal Service on August 2, 1861. While there may have been accidents, and maybe a secessionist shot or two during their tour, wounding men of the 6th, the majority of the casualties occurred in the Riot. This unit traveled through Baltimore to Washington and served its tour exclusively in that area, not participating in any conflict other than the Baltimore Riot during its tour. Surgeon Norman Smith was a member of this unit.

Col. Jones's 6th Regiment (Infantry) Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (MVM.) was a Massachusetts Militia unit, with organizational history going back to the 1630s. It's Civil War U. S. military service for was three months in 1861. The three year regiments were not Militia units, but were newly formed of enlistees and/or conscripts during the Civil War and were called Massachusetts Volunteers (Mass Vols). These then are the prime differences between the 6th MVM and the 6th Mass Vols organizations.

To my knowledge, Dr. Norman Smith was only involved in the Civil War with Col. Jones's 6th Regiment MVM.The next Massachusetts 6th Regiment was known as the 6th Regiment Infantry, Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (9 Months). Its term of service was approximately (the days differed for some of the men) August 31, 1862, to June 3, 1863. Surgeon Walter Burnham was the Surgeon of this unit.The next Massachusetts 6th Regiment was known as the 6th Regiment Infantry, Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (100 Days). Its term of service was approximately (the days differed for some of the men) July 16, 1864, to Oct. 27, 1864. Surgeon Walter Burnham was also the Surgeon of this unit.

From the Medical/Surgical History--Part I, Volume II

Chapter I.--Wounds And Injuries Of The Head.

Section II.--Miscellaneous Injuries.

An officer and eight men of the 6th Massachusetts Militia received contusions or lacerations of the scalp, by paving stones, bricks, etc., on the occasion of the memorable attack upon that Regiment by insurgents in Baltimore, on April 19th, 1861:

Privates G. Alexander, C. H. Chandler, and Sergeant W. H. Lamson, of Co. D; Sergeant G. G. Durrell, Co. D; Lieut. James F. Rowe, of Co. L; Privates S. Flanders, J. Porter, J. Pennell, and Charles B. Stinson, of Co. C. These patients were conveyed, by rail, to Washington, and were treated in the E Street Infirmary, under charge of Surgeon Norman Smith, 6th Massachusetts Volunteers, and the late Dr. J. Sire Smith, Assistant Surgeon, U. S. A.

Daily National Intelligencer, (Washington, DC) Monday, April 22, 1861; Issue 15,194; col A

The Excitement at Baltimore John W. Garrett, President.Note: At the bottom of this article, there is reference to the "Massachusetts Regiment Medicine Chest". A chest attributed to Norman Smith has surfaced in 2008-9 and attributed to Norman Smith. The markings on this 'fake' chest are not correct and are assumed to be a fake. See an example of that chest on this site.

Col. Jones's 6th Regiment (Infantry) Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (MVM.) was a Massachusetts Militia unit, with organizational history going back to the 1630s. It's Civil War U. S. military service for was three months in 1861. The three year regiments were not Militia units, but were newly formed of enlistees and/or conscripts during the Civil War and were called Massachusetts Volunteers (Mass Vols). These then are the prime differences between the 6th MVM and the 6th Mass Vols, organizations.

To my knowledge, Dr. Norman Smith was only involved in the Civil War with Col. Jones's 6th Regiment MVM.Source: Larry DeCan

Evidence of Norman Smith being the surgeon for the 6th at the Baltimore Massacre

Click on image to enlarge

6th Regiment Infantry (3 months Militia)

Tendered services to government January 21, 1861. Moved from Lowell to Boston in response to call of the President April 15, 1861. Left Boston for Washington, D.C., April 17 via New York and Philadelphia and to Baltimore April 19. Attacked in streets of Baltimore April 19. Reached Washington April 19 and camp in Capitol Buildings. Moved to Relay House May 5 and to Baltimore May 13, returning to Relay House May 16. Guard railroad until June 13. Duty at Baltimore and Relay House until July 29. Relieved from duty July 29, and mustered out August 2, 1861.

Lost 4 Enlisted men killed and mortally wounded.

Source: http://www.civilwararchive.com/Unreghst/unmainf1.htm

(1861 - 1865)

At the beginning of the Civil War, Pennsylvania Hospital received Philadelphia's first casualty, not from the battlefield but as a result of a secessionist mob action in a Baltimore railroad station. Attacking northern recruits, the mob set upon the Philadelphia contingent, including Private George Leisenring, who died four days later at Pennsylvania Hospital.

Source: University of Pennsylvania History

From the web: Source: Massmoments

January 21st, 1861, the Sixth Massachusetts Volunteer Militia was formally organized. With war approaching, men who worked in the textile cities of Lowell and Lawrence joined this new infantry regiment. They were issued uniforms and rifles; they learned to drill. They waited for the call. It came on April 15th, three days after the attack on Fort Sumter. They were needed to defend Washington, D.C. Washington was supposed to be in danger of capture by the Southern troops flushed with their victory at Sumter; armed and equipped soldiers were needed for its defense. When they arrived in the border state of Maryland three days later, everything changed. An angry mob awaited them. In the riot that followed, 16 people lost their lives. Four were soldiers from Massachusetts. These men were the first combat fatalities of the Civil War.In early January 1861, as civil war approached, the men of Massachusetts began to form volunteer militia units. Many workers in the textile cities of Lowell and Lawrence were among the first to join a new infantry regiment, the Sixth Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, when it was formally organized on January 21, 1861.All through the winter and early spring, the men met regularly to drill. In March, they were issued uniforms and Springfield rifles and told to be ready to assemble at any time. When Fort Sumter was attacked on April 12th, the men of the Massachusetts Sixth knew their days of drilling were over.

Three days later, President Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to serve for three months. They were ordered to Washington, D.C. to protect the capital and lead the effort to quash the "rebellion."

The Sixth Massachusetts gathered with other regiments in Boston on April 16th. The Lowell Daily Courier published one soldier's letter home: "We have been quartered since our arrival in this city at Faneuil Hall and the old cradle of liberty rocked to its foundation from the shouting patriotism of the gallant sixth. During all the heavy rain the streets, windows, and house tops have been filled with enthusiastic spectators, who loudly cheered our regiment . . . The city is completely filled with enthusiasm; gray-haired old men, young boys, old women and young, are alike wild with patriotism."

The Sixth Massachusetts Volunteers boarded trains the next day. One soldier reported, "Cheers upon cheers rent the air as we left Boston . . . at every station we passed anxious multitudes were waiting to cheer us on our way." In Springfield, Hartford, New York, Trenton, and Philadelphia, bells, fireworks, bonfires, bands, booming cannon, and thousands of supporters greeted the Massachusetts men as their train passed through.

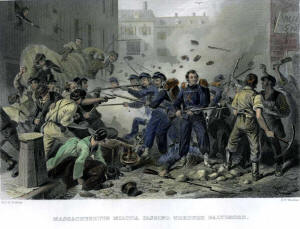

The mood changed dramatically when the train arrived in Baltimore on the morning of April 19th. Although the state had not seceded from the Union, many Baltimoreans were sympathetic to the Confederate cause and objected strenuously to the presence of northern soldiers.

Steam engines were not allowed to operate in the city limits, so the regiment crossed the city in train cars drawn by horses. Most of the men made it before a growing mob threw sand and ship anchors onto the tracks. At that point, the soldiers had no choice but to disembark and begin marching.

The commanding officer ordered the men to load their weapons but not to use them unless fired upon. An anxious corporal sent a note to a friend, "We shall have trouble today and I shall not get out of it alive. Promise me if I fall that my body shall be sent home."

Four companies of men from Lowell and Lawrence were separated by the crowd from the rest of the regiment. As they attempted to make their way through the city, angry citizens began to shout insults. As one soldier later told a reporter, we "were immediately assailed with stones, clubs and missiles, which we bore according to orders. Orders came . . . for double quick march, but the streets had been torn up by the mob and piles of stones and every other obstacle had been laid in the streets to impede our progress. . . . Pistols began to be discharged at us, . . . Shots and missiles were fired from windows and house tops. . . . The crowd followed us to the depot, keeping up an irregular shooting, even after we entered the [railroad] cars."

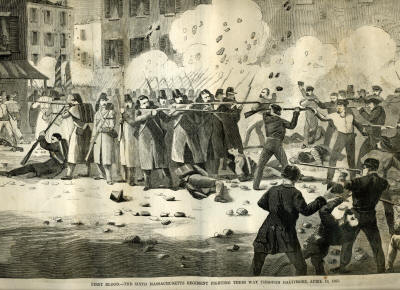

From Harper's Magazine, May 4th, 1861

"First Blood - The sixth Massachusetts Regiment Fighting their way through Baltimore, April 19, 1861"

Once the surviving members of the Sixth made it to safety, the mob returned to the station on the northern edge of the city. Nearly 1,000 more Pennsylvania and Massachusetts volunteers were waiting there. When the mob attacked, the soldiers moved into the streets. Pro-Union Baltimoreans joined the fight, and some offered to shelter the northern men. In the confusion, a number of soldiers gave up on getting to Washington and walked all the way back to Pennsylvania. (Scans available, please ask)

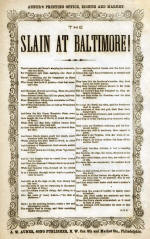

Twelve civilians lost their lives at what was later referred to as the Baltimore Pratt Street Riot. Four members of the Massachusetts Sixth, all from Lowell or Lawrence, were killed, including the apprehensive corporal. When the train finally arrived in Washington, two young women from Massachusetts who had been working in the nation's capital came to the station to nurse the injured — Clara Barton and her sister Sally Vassal. They took many of the wounded men to their home. Thus began the legendary nursing career of Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross.

(Scans available, please ask)

Back in Massachusetts, newspapers printed soldiers' accounts of the riot. "At Baltimore we heard no cheers, saw no waving of handkerchiefs," one man wrote, ". . . and not a smile greeted us. They gave out word that we could not pass through the city, that we should sacrifice our lives if we attempted it. But we received the order 'Forward,' and we did forward, in silence, carrying our flag unfurled. We were fired upon from all parts of the street. I heard the bullets whistle about my ears smartly. At last a stone took me in the head and knocked me down. But I got up immediately and discharged my musket at the rebels, and then kept on the march to the depot. I am here in the hospital with the rest of the wounded. My courage is still good. . . ." In 1865, the City of Lowell erected a monument to the three local men who lost their lives in Baltimore that day. Source: Massmoments via Google Books From Wikipedia, (mention of the regimental band, which confirms their presence and subsequent treatment by Dr. George Hewston in Philadelphia when they walked back to that city.)

On April 19, the Union's Sixth Massachusetts Regiment was traveling south to Washington, D.C. through Baltimore. At that time, there was no direct rail connection between the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad's President Street Station and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's Camden Station (ten blocks to the west) due to ordinances prohibiting the use of steam locomotives in the inner city and the lack of union stations at the time. Rail cars that transferred between the two stations had to be pulled by horses along Pratt Street.

As the regiment transferred between stations, a mob of secessionists and Southern sympathizers attacked the train cars and blocked the route. When it became apparent that they could travel by horse no further, the troops got out of the cars and marched in formation through the city. However, the mob followed the soldiers, breaking store windows and causing damage until they finally blocked the soldiers. The mob began throwing paving stones and bricks at the troops. Panicked by the situation, several soldiers fired into the mob, and chaos immediately ensued as a giant brawl began between the soldiers, the violent mob, and the Baltimore police. In the end, the soldiers got to the Camden Station, and the police were able to block the crowd from them. The regiment had left behind much of their equipment, including their marching band's instruments.

Four soldiers (Corporal Sumner Needham of Co I and Privates[4] Luther C. Ladd, Charles Taylor, and Addison Whitney of Co D) and twelve civilians were killed in the riot. Sumner Henry Needham is sometimes considered to be the first Union casualty of the war, though technically he was killed by civilians in a Union state. Needham is buried in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Ladd; Taylor and Whitney are buried in Lowell, Massachusetts.[5]

As a result of the riot in Baltimore and pro-Southern sympathies of much of the city's populace, the Baltimore Steam Packet Company also declined the same day a Federal government request to transport Union forces to relieve the beleaguered Union naval yard facility at Portsmouth, Virginia.[6]First Blood at Baltimore, from the Civil War Courier, March 2011

Documentation of the amputation performed by Norman Smith, M.D. in Washington, D.C. after the Baltimore Riot

Moses S Herrick Dr. Norman Smith's amputation patient 1861

Documentation regarding the uniform worn by Dr. Smith in the document photos

Norman Smith's Colt Dragoon pistol

Additional information on Dr. Norman Smith in his uniform

Return to the display of the Norman Smith surgical set

Documentation regarding the uniform worn by Dr. Smith in the photos

6th Mass. Vol. Militia and the Pratt Street (Baltimore) Riot at the start of the Civil War