BLOODLETTING ANTIQUES

DOUGLAS ARBITTIER, M.D.

The practice of bloodletting, or phlebotomy, dates back to antiquity. The followers of Hippocrates in the fifth century B.C. strongly believed in bleeding patients, and it is likely that this was done in Egyptian times and probably even before that. Early civilizations may have been inspired by seeing bats remove blood from animals, hippos scratching on trees until they bled, and other animals scratching at diseased body parts for relief. Additionally, there were many human examples of bleeding such as spontaneous nosebleeds and menstruation that had to be explained. It is perhaps these signs in nature that led early civilizations to put it all together: bleeding must have some beneficial value!

From these simple observations came increasingly complex theories as to why bloodletting was necessary and how it worked. An early theory was that there were four main bodily humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. An imbalance in these humors was postulated as the need for bloodletting, purging, vomiting, etc. Virtually every known medical condition at one time or another was treated by these methods. Bloodletting was used to treat everything from fever and madness to anemia and debility. As one can imagine, treating an anemic patient by removing even more blood was not the best of ideas. The popular belief that George Washington was bled to death proves that even "nobility" was not spared.

Through the Middle Ages and into the 18th and 19th century there were many strides in medical knowledge with regards to disease states, and anatomy. However, there was not much that could be done in terms of treatment. There were no antibiotics and surgery was in its infancy (in large part due to the lack of quality anesthesia). One of the only therapeutic modalities was to get out the old lancet and let some blood. It can safely be said that this almost never benefited the patient. Perhaps the biggest benefit was to the physician and family, who felt that at least they were doing something, and if the patient died anyway, it was meant to be.

Much detail is known about the history of bloodletting but an in depth study is beyond the scope of this summary. Instead, I will look at some of the artifacts that help to demonstrate how phlebotomy was carried out, both on humans and animals. Some of these items are still readily available on the antique market. Others are harder to find but do turn up from time to time. Most of these items are from the 18th and 19th centuries. Earlier items are essentially known only from illustrations.

THE LANCET

The earliest bloodletters probably used sharpened pieces of wood and stone to "breath a vein." There are many steel lancets with flat ebony or ivory handles that exist today (figure 1). There is some controversy surrounding these items. Firstly, though they are called lancets, they are thought by some to be ink erasers. Indeed, many have the signatures of stationers or cutlers that did not make surgical instruments. Some are unsigned. There are those who think that they were used for both purposes. Some feel that as bloodletting went out of favor in the late 19th and early 20th century the many leftover lancets were sold as "leftover stock" to stationary stores and sold as ink erasers. While I’m not sure of the truth, I feel that the commonly seen ebony-handled steel pointed instruments with clover leaf shaped blades were not used for phlebotomy. I just haven’t seen much evidence for their use in bloodletting.

A lancet that no doubt was used for bloodletting is seen in (figure 2). This is a standard 19th century thumb lancet in tortoise shell covers, or scales. These must have been made by the millions, mainly in England, but also in France, the US, and other countries. Some are signed with the maker’s name but many are either unsigned or just have a cutlers stamp. These items were standard equipment for physicians who made house calls. More decorative covers, in ivory and mother of pearl, can be seen in figure 3.

Thumb lancets were no doubt sometimes carried individually, but more commonly in a lancet case. These varied in form from simple leather boxes (figure 4) to beautiful engraved cases made of silver, mother of pearl, tortoise shell, and even gold (figure 5-7).

Figure 7 shows three unusual cases made in the orient for export to England around 1800. They have oriental scenes in relief, one made of silver, the others tortoise shell and mother of pearl. Often these cases had elaborate dedications from one physician to another, or perhaps from a patient who enjoyed being bled!

THE FLEAM

The fleam is perhaps easiest-to-find bloodletting antique. These devices have one or more blades at right angles to the handle. The most common form is a brass case containing 2 or 3 steel blades, often stamped with a makers name (figure 8). The blades were usually of various sizes to offer a selection to the phlebotomist. Many of these fleams were likely used on animals but the ones with small blades no doubt were used at times on humans as well. Imagine the farming family that used their fleam for both purposes! Figure 9 shows several fleams in horn casing. Some of these came with a removable thumb lancet inserted into the horn case.

Figure 10 shows 3 multi-bladed fleams in silver casing. These are unusual. One pictures a man walking over a bridge to a millhouse. This is French. The one on the left has the initials and family crest of Roger Manwaring of England and dates to the 1730’s. Figure 11 shows some crude fleams, probably of American manufacture and dating to the18th century.

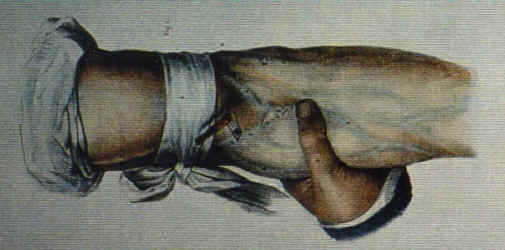

The fleams used for veterinary purposes were placed over the jugular vein of the neck most commonly and inserted with the help of a fleam stick. This was a heavy wooden club used to drive the blade in with a quick motion (so the horse didn’t know what hit him). Figure 12 shows a variety of fleam sticks. Often the bleeder would place a sheet over the animals head so they didn’t see what was coming. It’s a good thing they didn’t bleed humans this way!

THE SPRING LANCET

A much more elegant bloodletting method was used for humans. While fleams were sometimes used it was more common to use a spring loaded device in the 18th and 19th centuries. This is when the spring lancet was developed (though its origins go back earlier than this). Figure 13 shows a spring lancet in its simplest form. The case is brass and the blade is steel. The blade was cocked by the hook at end and released with the button on the side. Note the small size of the blade (for human use). Single blade spring lancets came in many sizes and shapes (figures 14-17). Most were brass and steel but some were made of iron or silver. Devices with larger blades were probably for veterinary use. Note the one with the depth adjuster. Figure 18 shows an unusual American hand-forged spring lancet that is signed "P.I.V. 1775." One wonders if the bleeder was anxious over the politics of the time as he bled his patients, whether human or animal!

THE SCARIFICATOR

Why bleed with one spring-loaded blade when you could have 4, 12, or even 20?! As long ago as the 17th century there were multi-bladed bleeders called scarificators. These became very popular in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Like spring lancets, they came in every size and description. Figures 19 and 20 show a basic octagonal English scarificator. The case is brass and the mechanism and blades are steel. There is a depth adjuster for the blades on the top and the blades are cocked by the lever on top. The release switch is on the side. This allowed the blades to swing around, making multiple cuts at once. Scarificators with pointed V-shaped blades are probably pre-1820. Those with slightly rounded blades are later. Round scarificators are usually French in design and post-1860 (often around 1900!) Scarificators that have a mechanism allowing the blades to stay in the half-cocked position are probably post-1830. Figures 21-24 show a variety of scarificators. Note the example of Tiemann’s patent 1846 scarificator with unusual horn handle in figure 23. This figure also show a rare solid silver scarificator made in England. Figure 24 shows the tremendous variation in sizes between these devices.

CUPPING

Once a scarificator was used to slice and dice the patient, a cup was often placed over the wound as a receptacle for the blood. Cups were made of tin, brass, rubber, horn, and most commonly glass. Figure 25 shows a selection of cups of various materials. There were often suction devices attached to the cup to allow the removal of blood. Human lips, rubber bulbs, and brass syringes were all used as sources for suction.

The above methods were for "wet cupping." At times "dry cupping" was used. This technique entailed creating suction in a cup placed over the skin without cutting the skin. Often a wad of burning material or the end of a heat lamp (figure 26) was placed in the cup to heat it. The cup was placed on the skin and a suction was created as it cooled. The skin then became engorged, presumably with evil humors that could improve health by coming to the surface.

All of the elements of wet and/or dry cupping were often placed in a complete kit, or cupping set. Figures 27, 28, and 29 show English (ca. 1860), American (ca. 1880), and French (ca. 1900) cupping sets respectively. These sets often had multiple cups, suction devices, scarificators, spare blades, etc. Figure 30 shows a very rare cupping set consisting of two matching scarificators and a heat lamp all in solid silver. Each is inscribed with the makers mark and owners initials. The pieces are hallmarked for 1832 and were obviously used by an important bloodletter!

BLEEDING BOWLS

From antiquity through the 19th century, there have been a large variety of vessels used to catch blood. These must originally have been made of stone or pottery. In the 18th and 19th centuries they were more commonly tin or pewter, though some rare silver examples are known. Figure 31 shows a variety of pewter bleeding bowls dating from about 1770 to 1850. These are of English manufacture. All of these bowls have inner concentric rings in ounce increments to measure the amount of blood. One must be very careful in collecting these antiques as often they are confused with porringers. These are pewter and often have two handles instead of one. Unscrupulous individuals have been known to add inner rings to porringers. While this is usually obvious upon close inspection, let the buyer beware!

LEECHES

A long-used alternative to the lancet or scarificator is the leech. Since antiquity in Greece, Rome and Syria, leeches have been used to suck blood from many sites on the body. Hirudinea Annelida was the favored European "strain" and Macrobetta decora was used in the US. Leeches have both male and female sex organs (fun fact of the day). They attach to the skin via 3 sharp teeth, inject an anticoagulant so the blood won’t clot, and then "fill up." A European leech could ingest several times the amount of blood as an American leech, so the colonists often imported them.

Leeches were carried in a variety of containers that are now sought after by collectors. Figure 32 shows two glass containers. The small one was for several leeches while the bigger bowl may have been used to dish out the leeches in a pharmacy. Note the everted lip of both containers. These were used to attach a cloth to prevent escapees. Of note, there is some controversy as to whether the larger type of container was actually used as a fish bowl. Some were on pedestals and there is evidence for both types of use. Seeing as one can’t be sure of its use, a safe approach in collecting is simply to not pay too much for a large glass leech container.

The two small pewter containers pictured in figure 33 are portable leech carriers. I call them "leech mailboxes" as the front door flips down to gain access to the leech. Note the holes in this door. This allowed the leeches to get enough air. Physicians may have put a few leeches in this pocket-sized container for house calls.

Perhaps the most beautiful leech containers are the large decorative ceramic containers with multi-colored floral and other motifs. These often are inscribed "leeches" in decorative lettering. They date to the mid-19th century for the most part. Figure 34 shows a fine example. Once again, one must be cautious in purchasing these as reproductions are now commonplace. The thousands of dollars that an original costs have made these repros very well done!

A variety of unusual "mechanical leeches" were made in the 19th century. These were spring loaded devices made to simulate a leech’s bite in order to bleed a patient. Figure 35 shows a rare patent model for an artificial leech made by Frederick Wolf in 1866. The spring was tightened and by a turning motion the cuts were made just as a leech would. The top of the device is then pulled back to evacuate the blood by suction. Ingenious! These devices were cumbersome to use and not popular for very long.

COLLECTING

As with all antiques over the last 20 years, bloodletting antiques have become harder to find. They can range in price from $20 for a lancet/ink eraser up to many thousands for a fine leech jar or rare cupping set. As mentioned several times, one must be very careful to avoid reproductions, which are becoming more commonplace. Some English dealers have gutted wooden boxes, relined them with old looking velvet, and made a "custom" cupping set which looks genuine and original. It’s scary, when one realizes the costs of these items.

There are specialty medical antique dealers and auction houses that have medical sales in the US and Europe. One can pay top dollar buying this way. A more reasonable way to get started is to scour country sales and local estate auctions. Cupping sets do appear from time to time as do spring lancets and scarificators. Often no one knows what these were used for and the price is quite low. There is nothing more exciting than finding a $200 item for $20 and this still can happen!!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANTIQUE MEDICAL INSTRUMENTS ANTIQUE MEDICAL INSTRUMENTS by C Keith Wilbur, MD., 1987.

ANTIQUE MEDICAL INSTRUMENTS ANTIQUE MEDICAL INSTRUMENTS by Elisabeth Bennion, 1979. by Elisabeth Bennion, 1979.

BLOODLETTING INSTRUMENTS in the NATIONAL MUSEUM OF HISTORY

AND TECHNOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGY by Audrey Davis and Toby Appel, 1979. by Audrey Davis and Toby Appel, 1979.

!!!!!!! IMPORTANT NOTE !!!!!!!

I am a very active collector of all sorts of pre-1900 bloodletting antiques in excellent condition. Over the years I have acquired most of the more common examples of the types things I reviewed in this paper. However, I am very seriously looking for unusual bloodletting devices, leeching items, and cased cupping sets. I purchase items individually or by the collection and am always eager to hear from other collectors. I do have some items for trade as well. If you have or know of any of these items for sale (I do pay finder’s fees) please contact me personally at any time via email. Thank you very much!

Doug Arbittier, M.D.