Civil War Army Hospital Microscopes by Joseph Zentmayer, or Grunow

There are articles or books which question the use of certain diagnostic instruments during the Civil War. An example of a Zentmayer Army Hospital microscope is used for illustration of this type diagnostic instrument used during the War. By examining the cases in the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, it can be shown by case documents that indeed the microscope was used during the War. And further more that books, such as Virchow's Pathology, (published by the Army Medical Department during the War for use by the Union medical staff), addresses microscopic pathology.

The Pillischer microscope below is one such microscope which would have been available during the War and is an example of the type and size used at the time. There were on a very few microscope makers in Ameria at the time of the Civil War, but many microscopes had been imported from England and Europe.

Microscopes being the unwieldy instruments they are, would have been available in the rear hospital areas, not in the field. An autopsy would have been done in a hospital and any microscopic examination would have been conducted under a controlled situation, not out of the back of a wagon or in a tent.

Above, An M. Pillischer claw-foot monocular microscope, London, c. 1860's

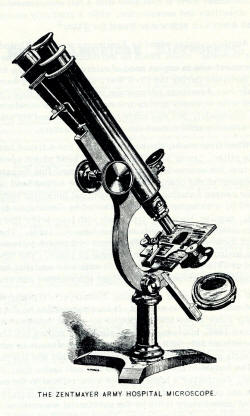

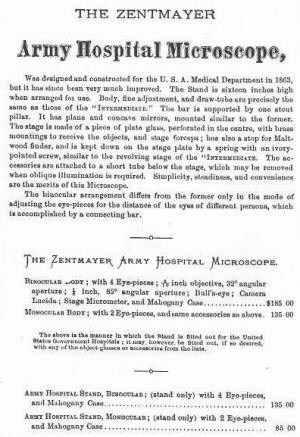

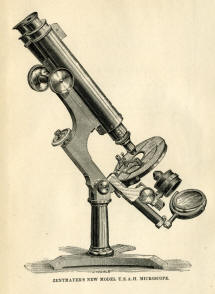

Earlier 1873 version on left, later version on right (from an ad in 1881 'Compendium of Microscopical Technology'. The 1873 example of the 'Army Hospital Microscope' by Zentmayer, was introduced in 1862.

In 1862, Zentmayer began building the U.S. Army Hospital microscope to meet the needs of the Civil War. This model was produced for over 30 years, undergoing many gradual modifications, until finally it had incorporated the swinging substage and redesigned limb and long lever fine focus patented by Zentmayer, and eventually even a horseshoe foot. Unlike the larger stand, the Army Hospital stand is commonly encountered today and must have been made in fairly large numbers. The cost of the basic Army Hospital stand in 1879 was $90, with the fully equipped binocular version going for $173.

The following ad was on the last page of: The Army Surgeon's Manual, by Wm. Grace, 1864

CASE.--Private Julius McKnight, Co. D, 27th U. S. Colored Troops, aged 23 years, received, on July 30th, 1864, at the siege of Petersburg, Virginia, a gunshot wound of the scalp. He was sent to the hospital for Colored Troops, a few miles in the rear, at City Point. Here little importance was attached to the wound of the bead, and the patient was entered on the register as suffering from remittent fever. On August 14th, he was sent to Philadelphia, to the Summit House Hospital, where the scalp wound was regarded as serious. As it was progressing favorably, light, simple dressings were applied. In September, symptoms of diphtheria were manifested, and the disease making very rapid progress, the patient died, on September 20th, 1864. At the autopsy, the mucous coat of the fauces and trachea appeared to be ulcerated and disorganized. A tough tubular membrane lined the larynx, trachea, and bronchi, even to the smaller ramifications; and in the larger air passages, this pseudo-membrane was detached. It was of a yellowish gray or ash colored tree. The lungs were much engorged. An abscess containing half an ounce of pus was found in the right lung. Entangled among the columnae carneae of the right ventricle of the heart was a concretion, half an ounce in weight, very similar in appearance to the membranous exudation in the lung. It was very unlike the ordinary fibrinous coagula or heart clots so frequently observed in autopsies, and tinder the microscope, presented the same histological elements as the exudations in the air passages. Surgeon J. H. Taylor, U. S. V.Examples of microscope usage during the Civil War from the Medical and Surgical History of the War of Rebellion

CASE.--Private William Rogers, Co. G, 7th Ohio Volunteers, aged 23 years, was wounded at the battle of Port Republic, Virginia, June 9th, 1862, by a conoidal ball, which struck the os frontis, one inch above the edge of the right orbit, and about half an inch from the median line. He was rendered insensible for a few moments, but soon recovered sufficiently to walk from the field. He was admitted to Cliffburne Hospital, Washington, on the 15th. The wound was healthy in appearance, and discharged a thin, sere-purulent fluid; the pulsation of the brain was distinctly visible, and splinters and loose fragments of bone could be felt. Absolute quiet was enjoined, and light diet and simple dressing, with aperients, ordered. On the 17th he complained of increasing pains. Assistant Surgeon John S. Billings, U. S. A., enlarged the wound of entrance, and removed the fragments of bone with forceps. The ball could not be found, it having evidently entered the brain. The wound was left open, and lightly dressed with wet lint. The patient felt better the next day. The second day after operation, he complained of slight, persistent pain in the back of the head, which continued until the 20th, when a small fungus growth made its appearance in the wound. Suppuration, which had previously been profuse and healthy, was much diminished, and the pain increased. The fungus was readily detached with the handle of the scalpel, and its removal gave exit to an ounce of pus, which somewhat relieved the pain. Hernia cerebri again appeared on the 27th, and death took place on the evening of the 28th. The patient was never delirious, and could answer questions correctly up to an hour before his death. The autopsy revealed the ball, much fissured and twisted upon itself, lying in a sac of false membrane, about one inch beneath the dura mater. The whole anterior lobe was broken down, and of a pultaceous consistence, dark sanious pus filling the ventricular cavity. The adventitious tissue, which formed the bulk of the hernia and the cyst containing the ball, was soft, and under the microscope was seen to be composed of interlacing fibres, containing large cells in its meshes. The history of the case was contributed by Assistant Surgeon John S. Billings, U. S. A.

CASE.--Sergeant James D. Hogan, Co. C, 1st New York Volunteers, was wounded at Manassas, Virginia, August 30th, 1862, by a conoidal ball, which entered two and one-half incites to the right of, and on a level with, the second lumbar vertebra, and lodged. He also received a gunshot wound of the right thigh. He was treated in the field, and, on September 3d, sent to Wolfe Street Hospital, Alexandria. No search was made for the ball as the patient assured the attending surgeon that it had been removed on the field. The wound seemed to heal, though very slowly until November 17th, when a small tent-like protrusion of exuberant granulations appeared, such as are usually seen at the orifice of a sinus leading to dead bone. The patient was unable to stand erect or lie on his back. The surrounding parts being considerably inflamed and the partially cicatrized wound reopening, a careful search was made for foreign matter. The ball was found about three inches from the point of entrance and removed by Acting Assistant Surgeon S. E. Fuller. The track of the missile was carefully explored and found to extend four inches in a direction forward and a little inward, where the point of the probe came in contact with spiculae of bone. There was considerable tenderness over the whole of the lumbar vertebrae, but no paralysis or other symptoms indicative of injury to the spinal cord. This man was discharged from service on December 29th, 1862, at which time he was improving rapidly, although he was still unable to stand erect. The specimen is No. 4486, Section I, A. M. M., and consists of an elongated smooth-bore musket ball, much roughened on one side. The incrustation on the missile exhibits, under the microscope, spongy bone. It was contributed by the operator. Pension Examiners Craig and Porter, of Albany, report that this pensioner's disability may be rated as "one-half and permanent." He had "much pain and weakness of the back" in July, 1871.

CASE 133.--Private Charles Caloney, company B, 34th New York volunteers; admitted July 7, 1862. Debility and diabetes. Died, August 21st. Autopsy next day: The lungs were healthy, except a few old adhesions attaching them to the costal pleura. The heart also appeared healthy, except that there existed an old pseudomembrane, about the size of a dime, adherent to the left ventricle near its apex. The pseudomembrane was fringed, the processes being about one-third of an inch in length. The liver appeared of the usual size and consistence, but was livid purple above arid slate colored below. The spleen appeared healthy. The stomach was moderately distended with air and liquid food; its mucous membrane was red in small spots, and there was a patch of inflammation about two inches square near the pylorus. The mucous membrane of the ileum was inflamed in patches; its solitary glands were prominent, and the agminated glands were red and inflamed, or were thickened and opaque white. The colon was distended with air; its mucous membrane presented small patches more than usually injected, arid its solitary glands were inconspicuous. The kidneys were below the average size, and their cortical substance was much paler than usual, the tint being pinkish cream colored. The microscope presented the usual condition of the granular cells, (i. e., there was no obvious fatty degeneration.) --Acting Assistant Surgeon Joseph Leidy.

Carditis and Pericarditis.--The comparative immunity from inflammation after injury, that we have observed in the parenchyma of the lung, when contrasted with the effects of wounds of its membrane, is yet more conspicuously displayed in the effects of mechanical lesions upon the heart and its serous envelope. Enough examples of wounds of the heart, in which the fatal issue was sufficiently delayed to afford time for the development of inflammatory phenomena, have been observed to warrant the conclusion that parenchymatous inflammation of this organ is as infrequently the result of injury as of disease.(3) I have examined two cases where patients survived a fortnight or more after shot wounds grazing the heart, in which the pericardium was thickened and the visceral as well as the reflected layer of the pericardium was thickly coated with shaggy exudations; but the muscular structure presented no alterations discernible by the microscope.(4) If an analogy might be instituted between the effect of tension on inflamed striated muscle in the trunk or extremities, it would be inferred that the slightest degree of inflammation of the muscular structure of the heart would cause unendurable anguish in its movements

CASE 810.--Private John W. Gardener, Co. F, 24th North Carolina, aged 25 years, was wounded at the battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862. A conoidal musket ball entered just above the pubis and passed out through the body of the ischium. He was sent to a hospital at Richmond, and, a week subsequently, was sent to his home in Cumberland County, North Carolina. He was admitted to the Fayetteville Hospital, November 1, 1863. Urine passed through the orifices of entrance and exit; there were bed-sores, with extreme emaciation, debility, and pain. With careful treatment the general condition

(1) The specimen is one-half of a nearly globular vesical calculus an inch in diameter. It weighs fifty grains Troy; the original weight of the entire calculus is unknown. Its exterior is of a slightly reddish gray, soft, porous, and granular. It is seen to be composed of a homogeneous structureless mass, presenting to one side of the centre a comparatively large irregular cavity, which wag originally filled with a soft pasty mass forming the nucleus of the calculus. It is of a muddy gray color, soft, granular, porous, and structureless throughout. A small quantity of the dust from the calculus heated on platinum blackened and cleared up with some loss, and dissolved in hydrochloric acid without effervescence; the solution neutralized with ammonia and treated with oxalate of ammonia gave no precipitate. A fresh portion was soluble in boiling water to the extent of about one-third of the quantity used; the residue was insoluble in liquor ammoniae, but readily dissolved on acetic acid, from which it was precipitated by ammonia as a gelatinous deposit containing numerous crystals of triple phosphate. The solution in boiling water gave a deposit on cooling; boiled with liquor potassae it gave off ammoniacal vapors; treated with hydrochloric acid it gave a precipitate which, under the microscope, was found to consist of crystals of uric acid. It may be inferred that about two-thirds of the calculus consisted of triple phosphate, and one-third of urate of ammonia.

(2) CHISOLM (J. J.), A Manual of Military Surgery, 3d ed., 1864, p 352.

There are dozens of examples, like those above, in the documents of the Medical and Surgical History texts which show repeated use of the microscope during the Civil War. This information was repeatedly found via a digital search for the word 'microscope'.