Note there is no brass plate on the top of the case and no provision for one, re-enforcing screws around the perimeter of the top of the case, and bilateral military sliding latches on the front

Military

sliding latches and re-enforced brass screwed lid

Interior velvet lining is green, the Tiemann label is 67 Chatham St.

|

Wanted: cased sets and individual instruments made by Kolbe, Brinkerhoff, Gemrig, Wade & Ford, Tiencken, George Tiemann, H. Hernstein, or Hernstein & Son. Incomplete or partial sets and individual instruments or paperwork by these makers are wanted to purchase for this collection. |

Civil War Embalming Surgeons

Embalming surgeons and undertakers were not always the same person. At the start of the Civil War, chemical embalming by injection was performed by men with medical training, since they were familiar with the process, these were the Embalming surgeons. Undertakers had to perform the various tasks of removing, transporting and preparing the dead for funerals. The medical embalmers associated themselves with the undertakers and offered their special techniques for a fee. Embalming surgeons could also make money as regular army surgeons or a regular doctor while Undertakers found extra money by also being cabinet or coffin and furniture makers. In this way he could make his own coffins which typically sold from $4-7. Embalming became a thriving business during the War and they often set up ghastly advertisements in the major cities.

A surgeon, Thomas Holmes, established himself as the father of modern-day embalming. The son of a wealthy merchant, he graduated from the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University in 1849. Prior to the war, he spent years researching a safer means to preserve cadavers for medical schools across the country; there were too many medical student deaths being attributed to contact with the toxic embalming solution during dissections. It wasn’t until the late 1850s that he stumbled upon what was then believed to be a safe, non-toxic embalming fluid that contained about four ounces of arsenious acid (arsenic) per gallon of water—a solution that immediately killed or halted the microorganisms responsible for decomposition—and immediately sold the product to undertakers throughout the country.

Holmes gained instant notoriety in 1861 with the death of Union Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, a good friend of President and Mrs. Lincoln, who had once served as an apprentice lawyer in Lincoln’s law office. Lincoln was so deeply affected by Ellsworth’s death that he planned a special service for the Colonel at the White House. Secretary of State William Seward commissioned Holmes to embalm the body and prepare it for the journey to the White House. During the funeral, the appearance of Ellsworth’s body brought the comment from Mrs. Lincoln that he looked “…natural, as though he were only sleeping.” Holmes’ services were now in high demand.

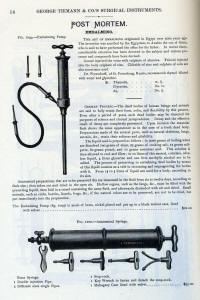

Holmes accepted a commission as captain in the U.S. Army Medical Corps and performed his trade first in Washington, DC, and then directly on the battlefield. After battle, he would erect an embalming tent and tend to the dead. His embalming table was crude and often consisted of a wooden door resting upon two barrels. Embalming was performed by squeezing a rubber ball that would pump the embalming fluid into the deceased’s artery (in the area of the armpit). This process took a couple of hours. There was rarely a need to drain blood, since that occurred naturally on the battlefield. When the embalming was complete, the body was then placed in a wooden box that was usually lined with zinc. On the lid appeared the name of the deceased along with his parent’s names. Inside were his personal belongings.

Holmes’ fee for embalming was $50 for an officer and $25 for an enlisted man. As the war continued, and embalmers were in high demand, those figures rose to $80 and $30, respectively. Feeling he could make even more money if he worked in the private sector performing the same duties, Holmes resigned his commission and began to charge $100 per embalming.

As surgeons and pharmacists became aware of the profits to be made from embalming, they traded in their instruments for that of an embalmer’s and followed the troops into war. After the battle, the embalmers would converge on the scene and quickly find dead officers to embalm, knowing that the family of an officer would be grateful and able to pay the embalming fee.

Richard Burr, a Union surgeon who served with the 72nd Pa. Volunteer Infantry, became an embalming surgeon when he saw the profit to be made. Known for severely inflating the price for embalming services, he created and distributed handbills after the battle of Antietam offering “Embalming for the Dead.” The handbill invited the curious to watch the procedure.

Embalming shed

Holmes claimed to have embalmed approximately 4,028 bodies during the Civil War. His supposed non-toxic embalming solution was indeed toxic and to this day continues to contaminate the soil in older cemeteries. Those who practiced embalming during the war returned to their hometowns and continued to perform the service in lieu of returning to their former trade. As for Dr. Holmes, prior to his death in 1900 he requested that he not be embalmed.

Most of the Federal soldiers who were killed in battle were quickly buried and, if time permitted, their burial places were marked with crude headboards. Due to the lack of identification, however, and with the enemy removing all valuables and clothing from the dead soldiers, it was often impossible to identify the remains.

As a result, almost half of all Federal dead soldiers were placed in graves marked ‘unknown.’ The government sent no coffins to the front, although coffins were furnished at large assembly points and at the general hospitals.

In the early part of the war, the cost of embalming was $50 for an officer and $25 for an enlisted man. Later, the price was increased to $80 and $30, respectively. One firm attempted to get a bill passed that would have given the firm exclusive rights to embalm the Federal dead. Another bill was introduced to Congress to authorize the creation of a corps of military undertakers for each division, but it failed to pass.

On the Confederate side, freelance undertakers and embalming surgeons were given safe passage between the lines, thus allowing them to ply their trade in Richmond as well as Washington.

Because of the lack of federal regulations governing undertakers, there were several cases of fraud and attempted extortion, so many that in March 1865 the War Department issued General Order Number 39, entitled ‘Order Concerning Embalmers.’ In part it read: ‘Hereafter no persons will be permitted to embalm or remove the bodies of deceased officers or soldiers, unless acting under the special license of the Provost Marshal of the Army, Department, or District in which the bodies may be. Provost Marshals will restrict disinterments to seasons when they can be made without endangering the health of the troops. Also license will be granted to those who can furnish proof of skill and ability as embalmers, and a scale of prices will be governed.’

Whatever embalming had been done prior to the Civil War seems to have taken place within the context of medical pathology, and was based primarily on sanitation, specimen preservation, and other needs in connection with medical studies of the human body.

The information above was compiled using information by James C. Lee, which originally appeared in the November 1996 issue of America’s Civil War; and from 'Embalming Surgeons of the Civil War, by James Willimam Lowry, as published by Tacitus Publications, 2001

Occurrences of 'Embalming' in the Medical and Surgical History database:

THE PENINSULAR

CAMPAIGN, VIRGINIA

March 17-September 2, 1862.(*)

No. 10. -- Report of Surgeon Charles S. Tripler, U.S. Army, Medical

Director, Army of the Potomac, of operations from March 17 to July 3.

On the 9th, Prof. Henry H. Smith, Surgeon-General of Pennsylvania, arrived with the steamer. Wm. Whildin, completely fitted up with bedding, stores, instruments, a corps of 18 surgeons and dressers, and a full complement of Sisters of Charity for nurses. He brought with him also the means of embalming the bodies of the dead. This kind office he cheerfully performed for numbers of men from other States. Surgeon-General Smith, upon being informed of my plans, entered into them with hearty good-will, and seconded them with an earnest zeal and a refreshing intelligence that showed he had not acquired his knowledge of hospital administration in Laputa. See more about Henry H. Smith on this site.

GENERAL ORDERS No. 7.

HDQRS. ARMIES OF THE UNITED STATES

City Point, Va., January 9, 1865.

* * * * * * * * * *

All embalming surgeons having been excluded from the lines of the armies

operating against Richmond, the friends and relatives of officers and

soldiers are hereby notified that hereafter the bodies of officers and

soldiers who die in general or base hospitals can be embalmed without

charge upon making personal application to the chief medical officer of

hospitals.

Applications for the embalming of officers and soldiers who die at

division hospitals at the front or on the field of battle must be made

to the medical director of the corps to which such officers or soldiers

belonged.

By command of Lieutenant-General Grant:

T. S. BOWERS,

Assistant Adjutant-General.

CASE 818.--Captain Richard H. Kimball, Co. K, 12th Massachusetts, was wounded, August 30, 1862, by a ball, which entered the right obturator foramen, passed through the bladder, and emerged through the left greater ischiatic notch, cutting the pyriformis. He survived the injury only a short time. The missile (FIG. 234) was cut from the gluteal muscles previous to embalming the body, and was placed in the Museum, with the foregoing memorandum, by Acting Assistant Surgeon F. Schafhirt.