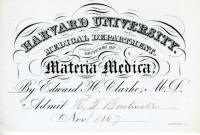

Edward H. Clarke, M.D.

Click image to enlarge

Sex in Education ; or, A Fair Chance for the Girls. By Edward H. Clarke, M. D., Member of the Massachusetts Medical Society ; Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; late Professor of Materia Medica in Harvard College, etc., etc. Boston : James R. Osgood and Company. 1873.

In this small volume Dr. Clarke takes up the discussion of one of the many important questions of the present day, the education of women, bringing to its treatment the result of considerable experience and that frankness of speech warranted by his position, which, although demanded for the full comprehension of the subject, has often been lacking in the writings of others upon this matter. For the proper consideration of sex in education it is necessary that there should be unreserved mention of certain phenomena which modesty bids should be generally ignored; but so long as reticence tends to allow the spread of harm, we should gladly welcome any plain words that may help to reduce the suffering that arises from ignorance. Dr. Clarke discusses a delicate subject, but, in general, only with what bluntness is required; in one or two places, however, the earnestness with which he denounces what he considers impending evils runs away with him, and the reader cannot help shrinking somewhat at his perhaps overdrawn description of the woman of the future.

But this is a trifling matter; of the book as a whole, the tone is excellent; more than that, the lesson it is intended to convey is one of the utmost importance, and the book cannot fail to do good; but we cannot help thinking that it would do more good, if we could have had from such an authority a full account of the prophylactic measures to be taken with regard to the health of our daughters, in addition to the warnings, useful as they are in many cases, winch the book contains.

In the beginning of his essay» Dr. Clarke states some physiological facts, which we need not repeat here, giving a brief and intelligible account of some of the peculiarities of the female constitution ; he goes on to urge that during the years of change from girlhood to womanhood, great caution should be exercised with regard to the amount of study demanded of the growing girl, for whom he recommends a system of rest at regular intervals, so that her brain need not be overworked at a time when there are unusual claims on the constitution, and that thereby such regularity of function be established as may secure a comfortable and healthy womanhood. For the support of his theories he brings forward a small number of selected cases from his note-book, such as every physician is familiar with in his practice, of women who, by gross disregard of hygienic laws, ruined or enfeebled their health.

That American women fade early is a matter of common observation; but that American women are so well educated that even a rigid following of the maxim Post hoc, ergo propter hoc, can ascribe the many cases of impaired health to over- study is not so patent. If we examine the variations from what would be recommended as obedience to the commands of physiology in the conduct of young girls, we find errors in dress, diet, and mode of life with regard to society and exercise, due to the carelessness and ignorance of both daughters and mothers. That young girls should be denied the use of books, and left to their own frivolity and to greater idleness, would be, in our opinion-, a lamentable result of Dr. Clarke's book, but one which it is to be feared will follow from what seems to us the undue stress laid upon the dangers of the employment of the mind on intellectual subjects. What Dr. Clarke says about the harm that may be caused by excessive brain-work is perfectly true, and true of men as well as of women. But it can only be said of the most excessive work, and to forbid well-regulated, moderate study from fear of such extreme consequences is no wiser than it would be to denounce all care of the health for the sake of avoiding valetudinarianism. Once in a great while we hear of a man who by long- continued application to intellectual work has, to all intents and purposes, emasculated himself; he is as unfit to be a father as an equally overworked woman would be to become a mother; the harm is as bad in one case as in the other ; but still we do not feel inclined to close our colleges, nor to warn ambitious youths against the deleterious influence of abstruse studies.

That there are delicate girls who often show more zeal for their lessons than their hardier brothers is very true, and to recommend the same course of study for both would be as unadvisable as to send them both out of doors to take the same amount of exercise every day in the year; such girls need to be treated with great care; their over-ambition may be one symptom of an unhealthy nervous condition, and the physician needs all his tact to determine the amount of brain- work they are to be allowed. But the same care is needed if his patient be a boy who is troubled, for example, with curvature of the spine. Ill health in any form demands particular care that no part of the body should be overtasked, and parents should be cautioned against allowing delicate children of either sex to injure their health by poring over books, as well as by sitting in draughts when over-heated, or by wearing insufficient clothing.

The general effect of education we cannot help thinking is undoubtedly good, and for girls quite as much as for boys. In the first place, it is absolutely indispensable, if women are at all anxious to adapt themselves for what is demanded of them by men who seek to make companions of their wives, and by their own wishes to be able to understand what is going on about them. To resist the demand that women are making for education is a hopeless task; but the opposition is doing good work by denning, modifying, and improving the claims that continually present themselves with renewed force. It is, of course, to be desired that the best methods of educating women be put in practice, and Dr. Clarke strikes with proper severity at some objectionable sides of education, which we shall discuss further on ; but so far as his book has a tendency to throw a doubt on the advantages of study for women, we think it demands correction. For, secondly, study, if properly supervised, that excess may be avoided, gives occupation to the mind at the time of its unfolding, when the young girl's curiosity is aroused, when she ceases to take an interest in childish things, and when, if worthy objects do not claim her attention, she is likely to devote it to things unworthy. At that time she learns with extraordinary facility, which, it is very true, is prone to tempt her to undue exertion; but so long as a teacher has the best interests of her pupil at heart, that may be easily controlled, — at least, that would seem the proper course to be followed, rather than the forbidding of all study. The facility she shows, and which is generally so much greater than that of her brother, who very often does not begin fairly to work for some years later, often not until he is busy with professional study, is to be found connected with her greater interest in her studies. If at this time she be taken away from school, it is very difficult for her to do satisfactory work without proper instruction, — we all know the listless way in which girls read history together, — and she is only too ready to transfer her interest from books to fashion-plates, from reading to dancing, from solid improvement to flimsy joys. It is at a very critical age that custom demands that a girl be taken away from school, and when, as is almost universally the case, she is hurried into society, where she goes to half a dozen balls a week, where she meets young men, dances with them in heated rooms to the sound of fascinating music, resting in unobserved corners, talking heaven knows what nonsense to these same youths, we have here a course of conduct which would seem to demand severer reprobation than do a quiet home life, regular hours, plenty of sleep, and the active mind employed on truly humanizing occupations, which have at least the one healthy physiological effect, that of making the student forget herself. It is impossible to shut a girl up in a dark room with no employment for four years, and it would seem to be self-evident that it were better to find such occupation as notoriously distracts the mind from undue reflection on distinctions of sex, — a subject of thought always liable to do harm, and never more than at so susceptible an age,—than to let one's daughter run riot amid those pleasures which make this especially prominent, with the social ceremonies we have described above, with perpetual twittering about so-called " beaux," and very possibly careless, indiscriminate reading. There is no need of immuring a girl away from the society of men, but there is a difference between freedom and license. Every physician knows the calming influence that intellectual work exercises over those who feel themselves too sensitive to the temptations of the world, and we cannot help recommending some serious occupation of that sort to girls during the critical years of their early womanhood, as best worthy of their attention, and, properly managed, most likely to save them from subsequent suffering. While a physician's experience tends naturally enough to make him look at all mankind, and more especially all womankind, as victims of disease, the fortunately large number of healthy men and women is not to be forgotten; and while they should all take warning, they should not all suffer for the errors of their brothers and sisters.