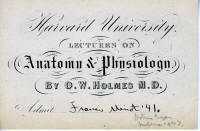

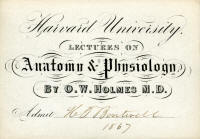

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. M.D.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, M.D. signed, Harvard University, Anatomy & Physiology, 1846, 1867

Click image to enlarge

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, professor, lecturer and author. Regarded by his peers as one of the best poets of the 19th century, he is considered a member of the Fireside Poets. His most famous prose works are the "Breakfast-Table" series, which began with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858). He is also recognized as an important medical reformer.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Holmes was educated at Phillips Academy and Harvard College. After graduating from Harvard in 1829, he briefly studied law before turning to the medical profession. He began writing poetry at an early age; one of his most famous works, "Old Ironsides", was published in 1830. Following training at the prestigious medical schools of Paris, Holmes was granted his M.D. from Harvard Medical School in 1836. He taught at Dartmouth Medical School before returning to teach at Harvard and, for a time, served as dean there. During his long professorship, he became an advocate for various medical reforms and notably posited the controversial idea that doctors were capable of carrying puerperal fever from patient to patient. Holmes retired from Harvard in 1882 and continued writing poetry, novels and essays until his death in 1894.

Surrounded by Boston's literary elite—which included friends such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and James Russell Lowell—Holmes made an indelible imprint on the 19th century literary world. Many of his works were published in The Atlantic Monthly, a magazine that he named. For his literary achievements and other accomplishments, he was awarded numerous honorary degrees from universities around the world. Holmes's writing often commemorated his native Boston area, and much of it was meant to be humorous or conversational. Some of his medical writings, notably his essay regarding the contagiousness of puerperal fever, were considered innovative for their time. He was often called upon to issue occasional poetry, or poems written specifically for an event, including many occasions at Harvard. Holmes also popularized several terms, including "Boston Brahmin" and anesthesia.

Having given up on the study of law, Holmes switched to medicine. After leaving his childhood home in Cambridge during the autumn of 1830, he moved into a boardinghouse in Boston to attend the city's medical college. At that time, students studied only five subjects: medicine, anatomy and surgery, obstetrics, chemistry and materia medica.[33] Holmes became a student of James Jackson, a physician and the father of a friend, and worked part-time as a chemist in the hospital dispensary. Dismayed by the "painful and repulsive aspects" of primitive medical treatment of the time—which included practices such as bloodletting and blistering—Holmes responded favorably to his mentor's teachings, which emphasized close observation of the patient and humane approaches.[34] Despite his lack of free time, he was able to continue writing. He wrote two essays during this time which detailed life as seen from his boardinghouse's breakfast table. These essays, which would evolve into one of Holmes's most popular works, were published in November 1831 and February 1832 in the New England Magazine under the title "The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table".[35]

In 1833, Holmes traveled to Paris to further his medical studies. Recent and radical reorganization of the city's hospital system had made medical training there highly advanced for the time.[36] At twenty-three years old, Holmes was one of the first Americans trained in the new "clinical" method being advanced at the famed École de Médecine.[37] Since the lectures were taught entirely in French, he engaged a private language tutor. Although far from home, he stayed connected to his family and friends through letters and visitors—Ralph Waldo Emerson, for example, visited one day—he quickly acclimated to his new surroundings. While writing to his father, he stated, "I love to talk French, to eat French, to drink French every now and then."[38]

At the hospital of La Pitié, he studied under internal pathologist Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis, who demonstrated the ineffectiveness of bloodletting, which had been a mainstay of medical practice since antiquity.[39][40] Dr. Louis was one of the fathers of the méthode expectante, a therapeutic doctrine that states the physician's role is to do everything possible to aid nature in the process of disease recovery, and to do nothing to hinder this natural process.[41] Upon his return to Boston, Holmes became one of the country's leading proponents of the méthode expectante. Holmes was awarded his M.D. from Harvard in 1836; he wrote his dissertation on acute pericarditis.[42] His first collection of poetry was published later that year, but Holmes, ready to begin his medical career, wrote it off as a one-time event. In the book's introduction, he mused: "Already engaged in other duties, it has been with some effort that I have found time to adjust my own mantle; and I now willingly retire to more quiet labors, which, if less exciting, are more certain to be acknowledged as useful and received with gratitude".[43]

After graduation, Holmes quickly became a fixture in the local medical scene by joining the Massachusetts Medical Society, the Boston Medical Society, and the Boston Society for Medical Improvement—an organization composed of young, Paris-trained doctors.[44] He also gained a greater reputation after winning Harvard Medical School's prestigious Boylston Prize, for which he submitted a paper on the benefits of using the stethoscope, a device with which many American doctors were not familiar.[45]

In 1837, Holmes was appointed to the Boston Dispensary, where he was shocked by the poor hygienic conditions.[46] That year he competed for and won both of the Boylston essay prizes. Wishing to concentrate on research and teaching, he, along with three of his peers, established the Tremont Medical School—which would later merge with Harvard Medical School[47]—above an apothecary shop at 35 Tremont Row in Boston. There, he lectured on pathology, taught the use of microscopes, and supervised dissections of cadavers.[48] He often criticized traditional medical practices and once quipped that if all contemporary medicine was tossed into the sea "it would be all the better for mankind—and all the worse for the fishes".[49] For the next ten years, he maintained a small and irregular private medical practice, but spent much of his time teaching. He served on the faculty of Dartmouth Medical School from 1838 to 1840,[50] where he was appointed professor of anatomy and physiology. For fourteen weeks each fall, during these years, he traveled to Hanover, New Hampshire, to lecture.[51]

On June 15, 1840, Holmes married Amelia Lee Jackson at King's Chapel in Boston.[52] She was the daughter of the Hon. Charles Jackson, formerly Associate Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and the niece of James Jackson, the pysician with whom Holmes had studied.[53] Judge Jackson gave the couple a house at 8 Montgomery Place, which would be their home for eighteen years. They had three children: Civil War hero and American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (1841–1935), Amelia Jackson Holmes (1843–1889), and Edward Jackson Holmes (1846–1884).[54]

After Holmes resigned his professorship at Dartmouth, he composed a series of three lectures dedicated to exposing medical fallacies, or "quackeries". Adopting a more serious tone than his previous lectures, he took great pains to reveal the false reasoning and misrepresentation of evidence that marked subjects such as "Astrology and Alchemy", his first lecture, and "Medical Delusions of the Past", his second.[55] He deemed homeopathy, the subject of his third lecture, "the pretended science" that was a "mingled mass of perverse ingenuity, of tinsel erudition, of imbecile credulity, and of artful misrepresentation, too often mingled in practice".[56] In 1842, he published the essay "Homeopathy and Its Kindred Delusions"[57] in which he again denounced the practice.

Charles D. Meigs, an opponent of Holmes's theory regarding the contagious nature of puerperal fever, wrote that doctors are gentlemen, and "gentlemen's hands are clean".[58]In 1843, Holmes published "The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever" in the short-lived publication New England Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Surgery. The essay argued—contrary to popular belief at the time, which predated germ theory of disease—that the cause of puerperal fever, a deadly infection contracted by women during or shortly after childbirth, stems from patient to patient contact via their physicians.[59] Holmes gathered a large collection of evidence for this theory, including stories of doctors who had become ill and died after performing autopsies on patients who had likewise been infected.[60] In concluding his case, he insisted that a physician in whose practice even one case of puerperal fever had occurred, had a moral obligation to purify his instruments, burn the clothing he had worn while assisting in the fatal delivery, and cease obstetric practice for a period of at least six months.[61] A few years later, Ignaz Semmelweis would reach similar conclusions in Vienna, where his introduction of prophylaxis (handwashing in chlorine solution before assisting at delivery) would considerably lower the puerperal mortality rate.

Though it largely escaped notice when first published, Holmes eventually came under attack by two distinguished professors of obstetrics—Hugh L. Hodge and Charles D. Meigs—who adamantly denied his theory of contagion.[62] In 1855, Holmes chose to republish the essay in the form of a pamphlet under the new title Puerperal Fever as a Private Pestilence. In a new introduction, in which Holmes directly addressed his opponents, he wrote: "I had rather rescue one mother from being poisoned by her attendant, than claim to have saved forty out of fifty patients to whom I had carried the disease."[63] He added, "I beg to be heard in behalf of the women whose lives are at stake, until some stronger voice shall plead for them."[64] The then controversial work is now considered a landmark in germ theory of disease.[27]

In 1846, Holmes coined the word "anesthesia". In a letter to dentist William T. G. Morton, the first practitioner to publicly demonstrate the use of ether during surgery, he wrote: "Everybody wants to have a hand in a great discovery. All I will do is to give a hint or two as to names—or the name—to be applied to the state produced and the agent. The state should, I think be called 'Anaesthesia.' This signifies insensibility—more particularly ... to objects of touch."[65] Holmes predicted his new term "will be repeated by the tongues of every civilized race of mankind."[66]

Teaching and lecturing

In 1847, Holmes was hired as Parkman Professor of Anatomy and Physiology at Harvard Medical School, where served as dean until 1853 and taught until 1882.[67] Soon after his appointment, Holmes was criticized by the all-male student body for considering granting admission to a woman named Harriet Kezia Hunt.[68] Facing opposition not only from student but also from university overseers and other faculty members, she was asked to withdraw her application.[69] Harvard Medical School would not admit a woman until 1945.[70] Holmes's training in Paris led him to teach his students the importance of anatomico-pathological basis of disease, and that "no doctrine of prayer or special providence is to be his excuse for not looking straight at secondary causes."[71] Students were fond of Holmes, who they referred to as "Uncle Oliver". One teaching assistant recalled: "He enters [the classroom] and is greeted by a mighty shout and stamp of applause. Then silence, and there begins a charming hour of description, analysis, anecdote, harmless pun, which clothes the dry bones with poetic imagery, enlivens a hard and fatiguing day with humor, and brightens to the tired listener the details for difficult though interesting study."[66]

Amelia Holmes inherited $2,000 in 1848, and she and her husband used the money to build a summer house in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Beginning in July 1849, the family spent "seven blessed summers" there.[72] Having recently given up his private medical practice, Holmes was able to socialize with other literary figures who spent time in The Berkshires; in August 1850, for example, Holmes spent time with Evert Augustus Duyckinck, Cornelius Mathews, Herman Melville, James Thomas Fields and Nathaniel Hawthorne.[73] Holmes enjoyed measuring the circumference of trees on his property and kept track of the data, writing that he had "a most intense, passionate fondness for trees in general, and have had several romantic attachments to certain trees in particular".[74] The high cost of maintaining their home in Pittsfield caused the Holmes family to sell it in May 1856.[72]

While serving as dean in 1850, Holmes became a witness for both the defense and prosecution during the notorious Parkman-Webster murder case.[75] Both George Parkman (the victim), a local physician and wealthy benefactor, and John Webster (the assailant) were graduates of Harvard, and Webster was professor of chemistry at the Medical School during the time of the highly publicized murder. He was convicted and hanged. Holmes dedicated his November 1850 introductory lecture at the Medical School to Parkman's memory.[72]

While dean, Holmes attempted to admit the first African-Americans and the first female to the Harvard Medical School. The same year, Holmes was approached by Martin Delany, an African-American man who had worked with Frederick Douglass. The 38-year-old requested admission to Harvard after having been previously rejected by four schools despite impressive credentials.[76] In a controversial move, Holmes admitted Delany and two other black men to the Medical School. Their admission sparked a student statement, which read: "Resolved That we have no objection to the education and evaluation of blacks but do decidedly remonstrate against their presence in College with us."[77] Sixty students signed the resolution, although 48 students signed another resolution which noted it would be "a far greater evil, if, in the present state of public feeling, a medical college in Boston could refuse to this unfortunate class any privileges of education, which it is in the power of the profession to bestow".[68] In response, Holmes told the black students they would not be able to continue after that semester.[77] A faculty meeting directed Holmes to write that "the intermixing of races is distasteful to a large portion of the class, & injurious to the interests of the school".[68] Despite his support of education for blacks, he was not an abolitionist; against what he considered the abolitionists' habit of using "every form of language calculated to inflame", he felt that the movement was going too far.[78] This lack of support dismayed friends like James Russell Lowell, who once told Holmes he should be more outspoken against slavery. Holmes calmly responded, "Let me try to improve and please my fellowmen after my own fashion at present."[79] Nonetheless, Holmes believed that slavery could be ended peacefully and legally.[80]

Holmes lectured extensively from 1851 to 1856 on subjects such as "Medical Science as It Is or Has Been", "Lectures and Lecturing", and "English Poets of the Nineteenth Century".[81] Traveling throughout New England, he received anywhere from $40 to $100 per lecture,[82] but he also published a great deal during this time, and the British edition of his Poems sold well abroad. As social attitudes began to change, however, Holmes often found himself publicly at odds with those he called the "moral bullies"; because of mounting criticisms from the press regarding Holmes's vocal anti-abolitionism, as well as his dislike of the growing temperance movement, he chose to discontinue his lecturing and return home.[83]

About 1860, Holmes invented the "American stereoscope", a 19th century entertainment in which pictures were viewed in 3-D.[95] He later wrote an explanation for its popularity, stating: "There was not any wholly new principle involved in its construction, but, it proved so much more convenient than any hand-instrument in use, that it gradually drove them all out of the field, in great measure, at least so far as the Boston market was concerned."[96] Rather than patenting the hand stereopticon and profiting from its success, Holmes gave the idea away.[97]

Soon after South Carolina seceded from the Union in 1861, Holmes began publishing pieces—the first of which was the patriotic song "A Voice of the Loyal North"—in support of the Union cause. Although he had previously criticized the abolitionists, deeming them traitorous, his main concern was for the preservation of the Union.[98] In September of that year, he published an article titled "Bread and Newspapers" in the Atlantic, in which he proudly identified himself as an ardent Unionist. He wrote, "War has taught us, as nothing else could, what we can be and are" and inspiring even the upper class to have "courage ... big enough for the uniform which hangs so loosely about their slender figures."[99] Holmes also had a personal stake in the war: his oldest son, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., enlisted in the Army against his father's wishes in April 1861[100] and was injured three times in battle, including a gunshot wound in his chest at the Battle of Ball's Bluff in October 1861.[101]

Holmes died quietly after falling asleep in the afternoon of Sunday, October 7, 1894. As his son Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., wrote, "His death was as peaceful as one could wish for those one loves. He simply ceased to breathe."[125] Holmes's memorial service was held at King's Chapel and overseen by Edward Everett Hale. Holmes was buried alongside his wife in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[126]

From Wikipedia, see the full article under his name on Wikipedia