Civil War Amputation Procedures

Stephen Smith, M.D. Handbook of Operative Surgery, 1863

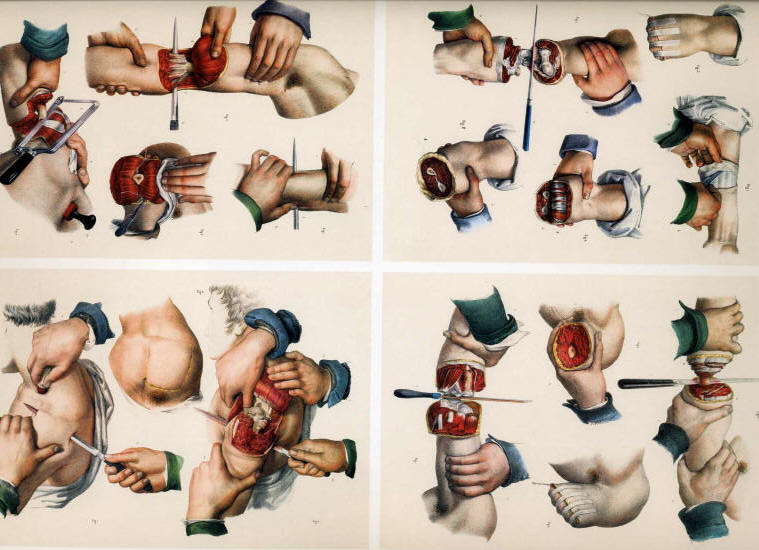

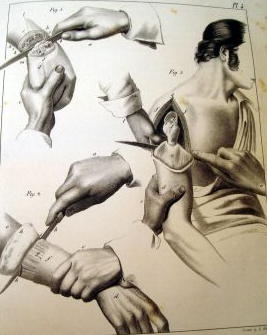

From from the medical textbook Handbook of Surgical Operations, U. S. A. Medical Department, 1863, (in this collection) written during the Civil War by Stephen Smith, M.D., with various drawings from the medical literature. Drawings from Bourgery & Jocob

AMPUTATIONS IN GENERAL

Amputations are performed through the shafts of bones, or through the joints; the former are said to be in the continuity, and the latter, in the contiguity.

Amputations In the Continuity: There are several methods of shaping the external parts to cover the stump in this operation :

Drawings from Bourgery & Jacob

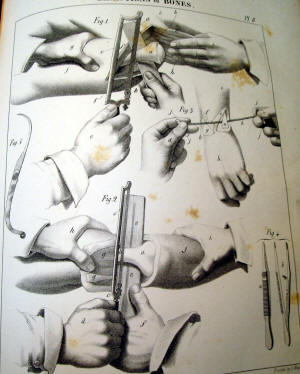

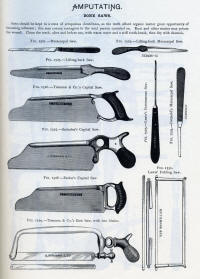

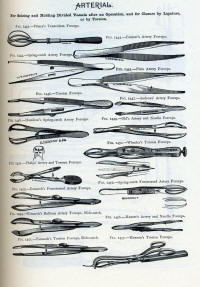

ORIGINAL PHOTOS OF INSTRUMENTS AND PROCEDURES FROM SMITH'S HAND- BOOK

Circular Method.—There are three principal steps in this operation:

1. Incision of the skin; 2. Incision of the muscles; 3. Section of the bone.

To incise the skin easily and neatly, the operator should stand upon the right side of the limb, the left foot thrown forward and placed firmly upon the floor, the right knee bending sufficiently to give freedom of motion to the body; the left hand grasps the limb -above the point of operation, and the handle of the knife is taken between the thumb and forefinger of the right hand, being lightly supported by the other fingers; stooping sufficiently to allow the right arm to encircle the limb readily, he carries the knife around until the blade is nearly perpendicular to the long axis of the limb on the side next to him with the point downwards, and the hand of the operator above the limb; he now commences the incision with the heel of the knife, giving slightly sawing motions, and brings the hand under the limb, and then directly upwards upon the side next to the operator, until the heel touches the point of commencement; the handle of the knife held thus delicately will change its relative positions as it passes around the limb without the slightest embarrassment to the operator; if the handle is firmly grasped in the whole hand, the incision cannot be completed without the aid of the other hand, or an awkward movement of the hand holding the knife; the ease with which the incision is completed will depend much upon whether it commences well down upon the side of the limb next to the operator. The skin is raised from the first layer of muscles by dissection, and drawn upwards, two or three inches, according to the diameter of the limb, like the cuff of a coat.

2. The first layer of muscles is divided at the margin of the retracted integument, in the same manner as the incision of the skin is executed; this layer is raised with the knife, and drawn still further upwards; and the last layer of muscles is divided down to the bone by the same sweep of the knife as before given. 3. The bone is then sawn at the apex of the cone.

Modifications.—The chief modifications are:—Louis divided the skin and superficial layer of muscles at one incision, drew them up and divided the remainder; Petit incised the skin, drew it up an inch, and then divided the muscles directly to the bone; Alanson dissected up the skin and then cut the muscles completely to the bone; Bell followed Alanson-, but concluded by detaching the muscles from the bone, an inch or more, with the point of a knife.

Flaps: Flaps may be anterior, posterior, or lateral; they may be made from without inwards, or from within outwards.

Single Flaps.—The operator grasps the tissues on the anterior part of the limb, with the left hand above the point of operation, and placing the heel of the knife at the point of the fingers on the opposite side of the limb, with a slight downward curve, he brings it over to the point of the thumb on the opposite side, with one stroke dividing the tissues to the bone; he now withdraws the knife until the point rests in the angle of the wound, when he thrusts it under the bone, taking care that the point emerges at the angle of the wound on the opposite side where the incision commenced ; he now makes a flap from the posterior part of the limb of sufficient length to cover the stump; the muscles are dissected from the bone with the amputating knife or a scalpel; the operation is very rapid, the knife not being raised from the limb.

Double Flaps: The operator grasps the tissues on the upper part of the limb with the left hand, the thumb and fingers resting at the middle of the limb on opposite sides; the knife, a, is then entered at the thumb and thrust through above the bone, emerging on the opposite side at the point where the fingers rest, and passed downwards and outwards, c, making an anterior flap, b, of the required length; it is again re-entered at the same point, and passing beneath the bone emerges from the same point on the opposite side, and a flap is made from the posterior part of the limb; both flaps are forcibly retracted, the muscles dissected from the bone, and the bone divided.

Modifications. Ravaton divided the soft parts circularly down to the bone, and then made two lateral incisions to the requisite extent and raised quadrilateral flaps; Sedillot first made two small flaps, turned them back, and completed the operation as in the circular method; Langenbeck made the flaps from without inwards.

Rectangular Flaps. First mark on the limb with ink two flaps; the size of the long flap is determined by the circumference of the limb at the place of amputation, its length and its width being each equal to half the circumference. The long flap is therefore a perfect square, and is long enough to pull easily over the end of the bone. In selecting the structures for its formation, such parts must be taken as do not contain the larger blood-vessels and nerves. The flap so formed will be for the most part anterior in position as far as regards the general aspect of the body, but superior when the patient is in the recumbent posture, as during the after treatment. The short flap, containing the chief vessels and veins, is in length one- fourth of the other. The flaps being formed, the bone sawn, and the arteries tied, the long flap is folded over the end of the bone; each of its free angles is then fixed by suture to the corresponding free angles of the short flap. One or two more sutures complete the transverse line of union of the flaps. At each side the short flap is united to the corresponding portion of the long one by a point of suture, and one suture more unites the reflected portion of the long flap to its unreflected (Fig. 95) portion. Thus the transverse of the union is bounded at each end by a short lateral line at right angles to it.

Oval Method.—In this operation the incision may be made like an inverted V, the apex being a little below the point where the bone is to be sawn; the incision being extended quite down to the bone before the lower portion of the flap containing the large vessels is divided; or a perfect oval may be marked out by the first incision, and the operation completed as in the former case. The oval method is seldom adopted except in amputation at the joints.

Amputations In the Contiguity.—The methods of amputation already described may be employed in the disarticulation of limbs. The instruments required are a single knife, having a narrow blade, to enable it to move more readily over the irregularities of the joint, with a thick back to give it 'firmness, and an artery forceps. The chief points to be well considered by the operator are thus concisely stated by Malgaigne (Operative Surgery, Am. Edition):

The operator has here three special objects in view: 1. To well recognise the articulation before commencing. 2. The flesh being divided, to traverse the articulation without hesitation, destroying all its means of attachment. 3. To preserve flesh and integument enough.'

Whence the following rules:

To Recognize the Articulation: The surgeon should have the disposition of the articulation so fixed in his mind, that he could, without having it under his eyes, trace it out exactly. In this way, recognizing one part of the articulation, he is sure of the others, neither the blood nor the soft parts causing the knife to deviate. He must also know the direction of the ligaments, to attack them more surely; their length, to cut them between their attachments; their breadth, to divide them completely.

1. The surest guides in finding the joints are the osseous projections. It is with them you must first occupy yourself. To find them, you may place the limb in a position that causes them to project; seek them on the side where they are most prominent; put aside by careful pressure the soft parts, fat, or oedema that mask their projections; and, lastly, seek them by starting from a known point: for example, passing the finger along the shank of a long bone till you reach its extremity.

2. The second indication consists in the folds of the skin, sometimes placed immediately above the joint, sometimes some way from it.

3. You may, as a third resource, cause to be prominent to the sight and touch the tendons which are inserted near the joint. To effect this, cause the muscles to contract; this is usually sufficient: or you may render their projection greater by opposing the movement of the limb which their contraction tends to execute.

4. If all these trials fail, you may assist yourself by the neighboring tuberosities, whether-or not they be in the same line, provided their distance and connexions are well determined beforehand. It is objected that the relations, and especially the distance, vary in different subjects; consequently, they can only give us a tolerably close indication: but certainly there is never more than some lines difference; and it is better to have such approximation than none at all.

5. If these means do not suffice, seize the limb with the right hand, and seek the joint with the left, moving the limb slightly, and thus try to mark out the two diameters of the joint, or, in other terms, the point of entrance and exit of the knife.

6. Lastly, supposing that all these indications do not afford a certain result, incise the skin in the most suitable direction, and, after having raised it, assure yourself by the touch of the articular line. If the touch does not point it out, place the knife in the angle of the wound nearest yourself, its heel perpendicular to the horizon, and the edge perpendicular to the bone, and thus move it along the bone with a sawing sidelong movement, without taking it off, and the pressure will cause the knife to enter the joint when it reaches it.

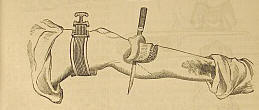

Use of the tourniquet, Liston amputation knife & capital saw

To Traverse the Articulation:

1. The articulation recognised, or at all events presumed to be so, as we have directed, the index finger and thumb should rest applied on the two extremities of the articular diameter until the knife replaces them. If this search has been made with the right hand, substitute the left hand for it before seizing the knife. In this way you mark the point of entrance and exit of the knife.

2. If you attack the joint by its dorsal surface, semiflex the limb, to extend the parts and enlarge the articular line. Without this precaution, you often fall on the neighboring joint, as happens on the foot and hand.

3. The knife should not generally be carried into the joint without having first cut its principal means of connexion, which should be divided from without inwards.

4. In joints with several projections and inter lockings, commence by the internal or external side. As the knife opens one joint, do not push it in there, but go on dividing and opening further. In this way, the ligaments are not put out of the reach of the knife, or shielded by bony projections.

5. An important fact. An articulation, that offers to the anatomist a surface equal to one inch, presents to the operator at least four. So long as the ligaments are divided between their attachments, it is of slight importance whether during their division the knife fall on the articular line or at the side of it.

6. The dorsal and lateral ligaments being cut, we can generally engage all the blade of the knife between the articular surfaces; but if there are interosseous ligaments, they must be first divided. Carry the point of the knife directly on them: as they are divided, the joint opens.

7. To destroy these ligaments, you must know the interstices between the bones through which they may best be attacked. In general, on the hand and foot, the bones, very compact on their dorsal surface, leave between them on their palmar and plantar surfaces intervals which lodge these ligaments. Carry the knife under these intervals, inclining the handle towards yourself, and making it form an angle of forty-five degrees anteriorly; then raise it up to a right angle. The ligaments divided by this movement allow the articulation to be opened sufficiently for the knife to enter it.

8. It is useless to luxate: it strains the parts very painfully; and if you separate the parts very much on one side, you apply those of the other together. If in cases of difficulty you have recourse to this means, luxate downwards as far as half the dorso- palmar diameter, and then vice versd. But it is better to separate the parts by slight traction parallel to the axis of the stump: this ordinarily suffices. The heel and point of the knife should always move in the same line. If, in bringing the knife out of the joint, you dread jagging the integuments, push them gently aside with your left forefinger and thumb.

To Preserve Sufficient Flap:

1. The proceedings vary according to the method, and often even in each method.

2. In the circular, you can generally count only on the skin to cover the surface of the wound. Make the incision at a sufficient distance from the joint, and dissect back the skin as a cuff. If there are muscles under it, you may cut them obliquely on the plan of Alanson, or divide them perpendicularly on a level with the joint.

3. The oval method is ordinarily performed by tracing on the dorsal surface a V incision reversed, the ends of which are joined by a semicircular incision round the palmar surface. When there are any large vessels, leave them in the portion to be divided last, as in the method by flaps, so as to be able to compress the artery before dividing it beyond the part compressed.

4. In most of the oval proceedings, the second incision is made to join the first at its point of commencement. A loss of substance is the consequence; or, if the V terminates on a level with th« articulation, there is considerable difficulty in getting the knife to act in disarticulating. I lay down here as a general rule, expose the joint to be destroyed by a longitudinal incision passing half an inch, at least, above, and one inch below it. The two branches of the V, which fall on the inferior part of this incision, leave, as it were, two small flaps at the-upper part, which do not hinder immediate and linear union, and which perfectly cover the osseous prominences left by the disarticulation.

5. The methods by one or two flaps are executed in two ways. Sometimes the flaps are made first, before touching the joint; but most usually a simple incision is made first, or the least important flap, and the second is not begun till after the disarticulation.

6. The knife having traversed all the joint, when the bones are large and uneven, as in the foot and hand, the instrument must be withdrawn, and its point placed horizontally in the extremity of the joint next the hand operating, and its way cut by pressing from right to left.

7. To avoid terminating the flap by a point, the knife must be held horizontally close to the bones, and kept so to the required extent, cutting freely.

8. It is well, before you terminate your flap, to apply it to the part to be covered, to see if it is long enough.

9. If there remain any tendons beyond the bleeding edge, cut them off with a scissors.

10. If you fear too much retraction of the skin, do not divide it until the muscles have retracted.

11. You may cut your flap from engorged tissues, so long as the engorgement is not malignant.

12. You may operate when there is not enough skin to make a flap; a cicatrix will be formed on the articular surfaces."

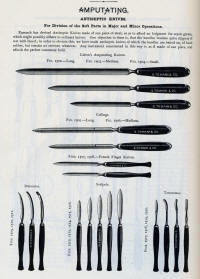

Instruments: The following instruments are required to form a complete amputating case:—A long and short knife, catling, metacarpal saw, scalpel, tenaculum, saw, bone forceps, artery forceps, needles, and tourniquet.

(Instrument drawings are from the 1880's Tiemann Catalog, other examples are from a Civil War military Hospital Department surgical set by Hernstein)

Knife, Catling, and Scalpel: The knife, a, selected for each operation should be of about twice the length of the diameter of the limb; the catling, is a double-edged knife, the two edges being parallel until they converge to form the point; the scalpel, is large and strong, having a firm handle.

The Saw: The form of saw generally used is represented in Dr. Wood's case; the edge should be straight, the teeth fine, and so set as never to allow the saw to bend in its passage through the bone; a saw having fine teeth is but little liable to lacerate the periosteum, and produces a comparatively small amount of comminution of the osseous tissue.

Bone Forceps: The forceps in common use is that of Liston.

In addition to the common artery forceps a pair of small forceps will sometimes be found useful in dissecting out vessels. Tourniquet

Arrangements.—The retractor is a piece of muslin, half a yard long, and half an inch wide, split in the centre, half its length; it is used by passing the tails on either side of the bone, and the extremities being seized by an assistant, the flaps are forcibly drawn upwards. The sponges should be fine, and in large number. These preliminaries being arranged, the patient is placed in a recumbent position, on a table of such height as to enable the operator to manipulate with his instruments about the limb with perfect freedom ; if it is an amputation by the circular method the limb should be much more elevated than if the flap operation is performed. The anaesthetic is administered by an assistant, and when the patient is under its influence a second assistant applies the tourniquet as directed, page 26, but as far as possible from the point of operation; previously to its being tightened, if it is desirable to save to the system the largest possible amount of blood, the limb is elevated and rubbed towards the heart to force the blood in the superficial veins beyond the point of amputation; compression of the artery by the fingers of an assistant should never be relied on when a tourniquet can be used. A third assistant should hold and steady the extremity of the limb, and a fourth is in waiting to retract the flaps, either with his hands or with the retractor, and to apply ligatures; a fifth uses the sponges. It is usual to have an assistant to hand the instruments to the operator, but it is much better and more convenient for the operator to place the instruments which he will require on a low bench by his side, in the order of the steps of the operation; an assistant frequently mistakes the instrument called for, and by his confusion often delays vexatiously an important step of the operation. The operator takes a position, in general, upon the right side of the limb. In amputations of the leg, however, the best position for sawing the bones is on the inside.

Operative Procedure.—An amputation in the continuity involves the following steps:

Incision of Soft Parts.—-The method being selected, the operator proceeds, according to the rules already given, to form the coverings of the bone from the soft parts; the bone having been exposed, an assistant, cither with his hands or the retractor, draws the flaps firmly upwards and maintains them in that situation.

Incision of the Bone.—The periosteum having been divided completely around the bone, as high up in the flap as possible, the saw is employed, in imitation of the cabinet-maker, the heel being first applied, and the saw drawn slowly but firmly across the bone to make a groove in which it will work, and then moved with as much rapidity as the operator may choose, until the bone is nearly divided, when it is to be moved more slowly to avoid splintering the last connexions. With the bone forceps any sharp or projecting edges are clipped off, and the end of the bone bevelled smoothly. Where there is a single bone it will be found easier to apply the saw nearly perpendicularly on the side opposite to the operator; where there are two bones the saw should be first and last applied to the larger and firmer bone, the smaller bone being completely divided while the saw is engaged in the larger bone.

Ligating Arteries.—The arteries should be tied according to the rules given, page 31. If a vein bleeds freely, a ligature should be applied. Before the stump is dressed any dark clot on its face should be removed, and a bleeding vessel sought for underneath it.

Dressings.—The flaps should be brought accurately together, and maintained by silk or metallic ligatures; the sutures should be taken deeply in the lips of the wound, from a quarter to half an inch, and at sufficient intervals to support the parts in apposition, with the assistance of adhesive straps applied in the intervals. The external dressings should be light and cool; the limb is then placed in an elevated position, and protected from all pressure and irritation.

FOR THE ORIGINAL PHOTOS OF INSTRUMENTS AND PROCEDURES FROM SMITH'S HAND- BOOK, CLICK HERE

Article on suturing during the Civil War

Article on anesthesia during the Civil War

Article on ligation of an artery during the Civil War