Ligation of Arteries During the Civil War

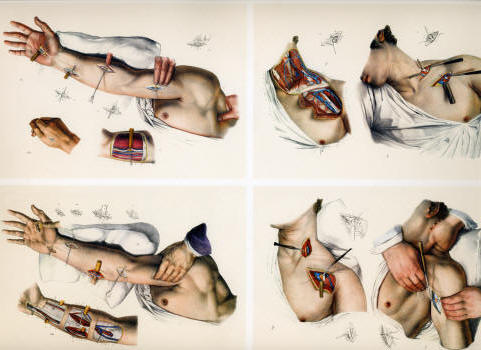

Edited from the medical textbook Handbook of Surgical Operations, U. S. A. Medical Department, 1863, (in this collection) written during the Civil War by Stephen Smith, M.D. Civil War medicine diagrams from Bourgery & Jocob.

LIGATION OF ARTERIES

The object sought in the ligation of an artery is the permanent obstruction of the current of blood by the obliteration of its cavity. To effect this object the internal coats of the vessel should be ruptured by the ligature; the process of obliteration then consists in the organization of the clot in the vessel with the adhesion of the ruptured tunics.

Instruments: The instruments immediately required are a scalpel, forceps, aneurismal needle, ligature, director, and spatulas.

The Scalpel: The common scalpel answers the best purpose in this operation. Its blunt, rounded edge, is best adapted to the dissection, and the broad extremity of the handle can be used to advantage in separating layers of fascia, and parts where the cutting edge is not desirable.

The Forceps: The common dissecting forceps should be selected for the dissection; they should have accurately fitting teeth, and not be liable to open at the extremity when firmly closed; a pair of small forceps may also be required.

The Needle: The common aneurism needle is a curved blunt instrument, with an eye near the extremity, and firmly fixed in a handle (Fig. 51). When used, the extremity is gently insinuated under the vessel, and as it appears upon the opposite side, the loop of the ligature is seized with the forceps, or a hook, and one end being drawn through, it is held as the instrument is withdrawn, carrying the other end, and thus leaving the ligature under the vessel. Of the different needles invented for this operation, that known as the " American needle," of Dr. Mott, is, perhaps, the most convenient, and is especially well adapted to those cases where the artery lies very deeply. It consists of the handle and hook and the blunt needle with two eyes .

Mott's "American" aneurism suture set with removable screw mounted tips as found in a typical Civil War surgical set

The needle is fitted to the shank by a screw mount. When used, the ligature is first inserted into the second eye; the needle is then passed under the artery, and as the extremity emerges upon the opposite side, the hook is inserted into the eye, and the needle is thus held until the handle is unscrewed, when it. is drawn through with the ligature. It is sometimes necessary to include other tissues with the artery, when the sharp-pointed needle is used.

The Director. The director is used in the dissection to raise the fascia before its division; it is sometimes passed under the artery as a guide to the needle.

Spatulas. Two spatulas are often required, with which assistants separate the sides of the wound, and expose the deep- seated parts; pieces of flexible metal or wood may be used.

The Ligature. The ligature is generally of the strongest dentists' silk, or of silver wire; its size proportionate to the size of the vessel.

Arrangements. The patient is placed upon a firm bed or on a table, and the assistant administers the anaesthetic; the surgeon takes his position generally on the outside of the limb which is the seat of the operation; a second assistant takes a position where he-can command the artery above if by any accident it is wounded, or if the artery yields under the tightened ligature; a third uses the sponges; and a fourth separates the wound with the spatulas.

Position of the Artery. The precise location of the artery is determined, 1. By its pulsations; 2. By given anatomical points in the vicinity. To render the former distinct, the limb should be placed in a position favorable ' to arterial circulation; to render muscles and tendons most distinct the limb should be forcibly extended at the commencement of the operation. When the dissection has proceeded so far as to reach the vicinity of the artery, the operator is aided in detecting its position by flexing the limb so as to relax the muscles and tissues.

Position of Superficial Veins. It is important, before the first incision is made, to guard against wounding superficial veins. Their position is readily defined by compressing the parts above the point of the proposed operation.

Operative Procedure. The operation involves several consecutive steps: Incision: When the first incision is about to be made, the skin should be rendered tense by the thumb and fingers of the left hand applied on either side of the vessel, or the fingers applied at the extremity of the proposed incision, parallel to its course; if the first method is chosen, care must be taken not to make more traction on one side than on the other; the second method answers where the skin is naturally tense and but slight traction is necessary.

The scalpel should be held in the second or third position, and the incision should be made directly over and generally parallel to the artery, through the skin only if the artery is superficial, but also through the cellular tissues if it is deep, ita length varying with the depth of the vessel and the fleshiness of the subject. The incision is sometimes made in the direction of the fibres of the muscle covering the artery, as where the great pectoral overlies the axiliary; at other times it should be curved, so as to raise a flap. The length of the incision cannot be prescribed, but it should always be ample.

Dissection of Fascice and Muscles: The fasciae are carefully pinched up with the forceps, and being opened with the scalpel applied horizontally, are incised freely on a director introduced beneath them. In dissecting among muscular structures it is important to enter the muscular interstices, and not wound the substance. These inter-muscular spaces are marked by deposits of fat, especially towards the terminal extremity of the muscles, and hence we should commence the separation of muscles as nearly as possible at their terminal extremity. If there is doubt as to the line of separation, a puncture with the bistoury will disclose adipose or muscular tissue, according to the nature of the underlying structure. If the dissection is made through the body of the muscle, the fibres separate more readily in an inverse direction, viz. from their origin to their attachments. The muscles may be separated with the handle of the scalpel or the finger nail.

Isolation of the Artery: The larger arteries have firm sheaths, which require to be opened by dissection; the smaller vessels have but slight fibrous investments, and are readily exposed with the point of a director, or the aneurism needle. The true sheath of the artery is opened by pinching up a small portion with the forceps, and nicking it slightly with the scalpel, held as before noticed; into the opening thus made, the end of a director or the aneurism needle is gently insinuated, and by slight movements of its point, first upon one side and then upon the other, the sheath is separated completely around the vessel, to an extent sufficient to allow simply the passage of the ligature; as the extremity of the instrument emerges on the opposite side, the finger of the left hand, or the thumb and forefinger pressed together, should steady its point as it penetrates the last of the investing sheath.

Passage of the Ligature.—If the artery is small and very superficial, a director may be passed under, and along its groove a blunt needle carrying the ligature. If more deeply situated-the common aneurism needle or the American needle should be used.